Future Generation Art Prize 2021

The PinchukArtCentre presents an exhibition of the 21 shortlisted artists for the 6th edition of the Future Generation Art Prize. Running from September 25, 2021 to February 27, 2022, the show gives a remarkable view on the artistic vision from the next generation of artists. Established by the Victor Pinchuk Foundation in 2009, the Future Generation Art Prize is a biannual global contemporary art prize to discover, recognize and give long-term support to a future generation of artists all over the world.

Featuring new works from all artists, the exhibition explores the world we live in today and how past experiences compel us to face a more inclusive future. Geopolitics is a recurring theme, with an emphasis on the global flows of labour, capital, and technology; the works reflect upon the unhealed scars of colonisation, ongoing conflicts, and the gradual exhaustion of natural resources. This close relationship to the natural world introduces a line of spiritualism within the exhibition that suggests the artist’s intangible or physical practice as a tool to care for each other’s communities. The interhuman relations become a crucial point for a whole number of projects, including the fragile intimacy and tension of queer identity.

The shortlist of the Future Generation Art Prize 2021 includes: Alex Baczynski-Jenkins (UK), Wendimagegn Belete (Ethiopia), Minia Biabiany (Guadeloupe), Aziz Hazara (Afghanistan), Ho Rui An (Singapore), Agata Ingarden (Poland), Rindon Johnson (USA), Bronwyn Katz (South Africa), Lap-See Lam (Sweden), Mire Lee (South Korea), Paul Maheke (France), Lindsey Mendick (UK), Henrike Naumann (Germany), Pedro Neves Marques (Portugal), Frida Orupabo (Norway), Andres Pereira Paz (Bolivia), Teresa Solar (Spain), Trevor Yeung (China), and artist collectives Calla Henkel & Max Pitegoff (USA), Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei (Ukraine), and Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings (UK).

Curator: Björn Geldhof, artistic director of the PinchukArtCentre. Assistant curators: Oleksandra Pogrebnyak and Daria Shevtsova.

Federico is an 8-minute choreography for two performers touching hands. Baczyński-Jenkins’ choreographies engage with queer affect, embodiment, and relationality. Through gesture, collectivity, touch, and sensuality, his practice unfolds structures and politics of desire. Relationality is present in the dialogical ways in which the work is developed and performed, as well as in the materials and poetics it invokes.

This includes tracing relations between sensation and sociality, embodied expression and alienation, the textures of everyday experience and latent queer archives. He approaches choreography as a way of reflecting on the matter of feeling, perception, and collective emergence.

His artistic practice extends into his experience as the co-founder of the Warsaw-based queer feminist collective Kem, which focuses on choreography, performance, and sound, at their interface with social practice. Through various experimental formats and community building, Kem engages in critical intimacy and queer pleasure.

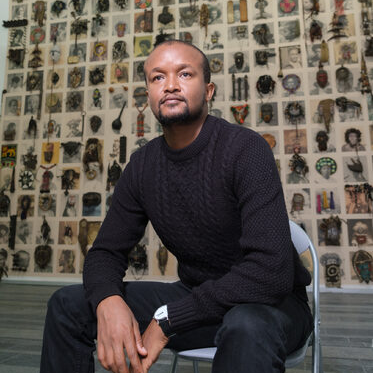

Wendimagegn Belete’s installation for the Future Generation Art Prize 2021 continues his exploration into questions on how history, memory, and identity are formed and constituted, and the concept of epigenetic inheritance, a memory that transfers over generations.

In the form of a large-scale mural, the work includes archival portraits taken during the second Italo-Ethiopian war (1935-1941). Ethiopia not only survived the invasion and won the struggle, but as a result it was honored as a country that was never colonized when the pan-African movement adopted the color scheme of Ethiopia’s historical flag. Collected from the digital archives, the photographs are conspicuously missing information about the depicted figures, a feature that highlights the risk of the individuals losing connection with their context and fading from collective consciousness. The work attempts to not only capture the memory of the person and the specific historical moment, but also transform the immaterial digital representation into a physical object. The grid composition is inspired by traditional Ethiopian painting and also serves as a visual expression of interdependence and harmonious coexistence, while the scale of the work creates an immense physical presence that elevates the forgotten individuals to almost heroic status.

Creating a further layer, a collection of objects is placed over the photographs. Originating not only from Ethiopia, but also from other African countries, they create a visual diversity that intentionally detaches the narrative of the work from one specific location in order to resonate with wider context. The process of assembling each photo with the accompanying objects involves both a conscious and subconscious approach, tapping into the idea of inherited memories which might surface through artistic gestures or linger in the materials themselves.

Your Gaze Makes Me weaves together digital and physical archival material to create a dynamic visual library that holds stories from the past and present, while also gesturing towards a more inclusive future in terms of the way we approach both history and art.

In the practice of Minia Biabiany, drawing within space represents a thinking process and a way to interact with one’s perception in an active and guided way. For the Future Generation Art Prize 2021, she presents an onsite installation directing the circulation of the spectator through the room. How is the perception of the space shaped by our own story, both externally, as in the movement of the body through it, and internally, as in the way it is perceived by the body? For several years, the artist has been interested in understanding her own system of forgetting and its relationship with the land in which she lives. Referring to the history of Guadeloupe, she investigates the traces of the plantation slavery system within her, as well as the tools available for recreating relationships with the territory and context in spite of its present day colonial situation — a Caribbean archipelago still controlled by France and actively assimilated into French culture.

The specificity of the guadeloupean context is expressed within the installation by the use of figures and metaphors, such as the patterns of traditional weaving technique that the artist links with conventional storytelling — the sea as it connects the islands, or the flowing water of the river, the active volcano La Soufrière or the constant wind from the Atlantic ocean, the soil polluted by pesticides used on banana plantations… All are parts of the environment in which the artist lives and which she turns into a poetic and political storyline. She understands the reinvention of the autonomous relations between forces and people as part of her own search for healing and the process of resistance.

Dividing the room and forcing the viewer to walk on only certain paths, Biabiany creates small observation events and turns them into parts of the extended body, displaying different densities and rhythms, much like a breathing pattern. Both the bodies and the colonial system she observes become spaces of autonomous learning by allowing the viewer to observe their own sensations.

Aziz Hazara focuses in his artistic practice on issues of memory, identity, archive, loss, and trauma. Appealing to the history of his native country of Afghanistan, he explores the effect that war and military conflict have on the life of individuals.

In the multichannel video installation Bow Echo, the title of which refers to a dangerous and destructive storm, five boys resist the wind by attempting to blow a bright plastic bugle. Their act represents the story of repression and suffering that their community has experienced unabated. In contrast, however, to the tradition of sounding a bugle in remembrance of those who have lost their lives, the notes of this flimsy instrument appear quite powerless. The sound blurs together with the noise of the wind and approaching drones.

Against the forces of nature, the boys’ efforts to play the bugle and hold their ground on the rocks seem incredible. Their fragility and insecurity become even more pronounced against the background of the mountain landscape of Kabul, now the site of their traumatic experience. Through pure picture and sound, Hazara creates a monument to the dramatic and violent struggle that generations of people in Afghanistan have experienced in the never-ending war.

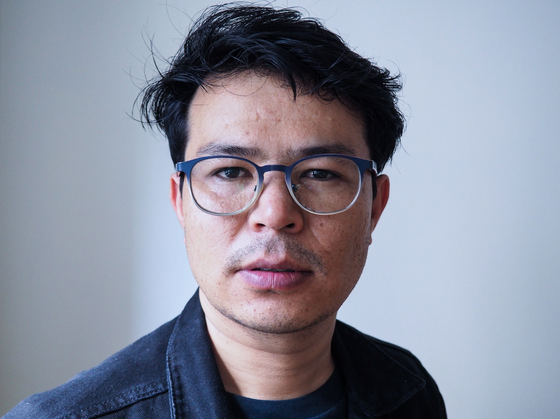

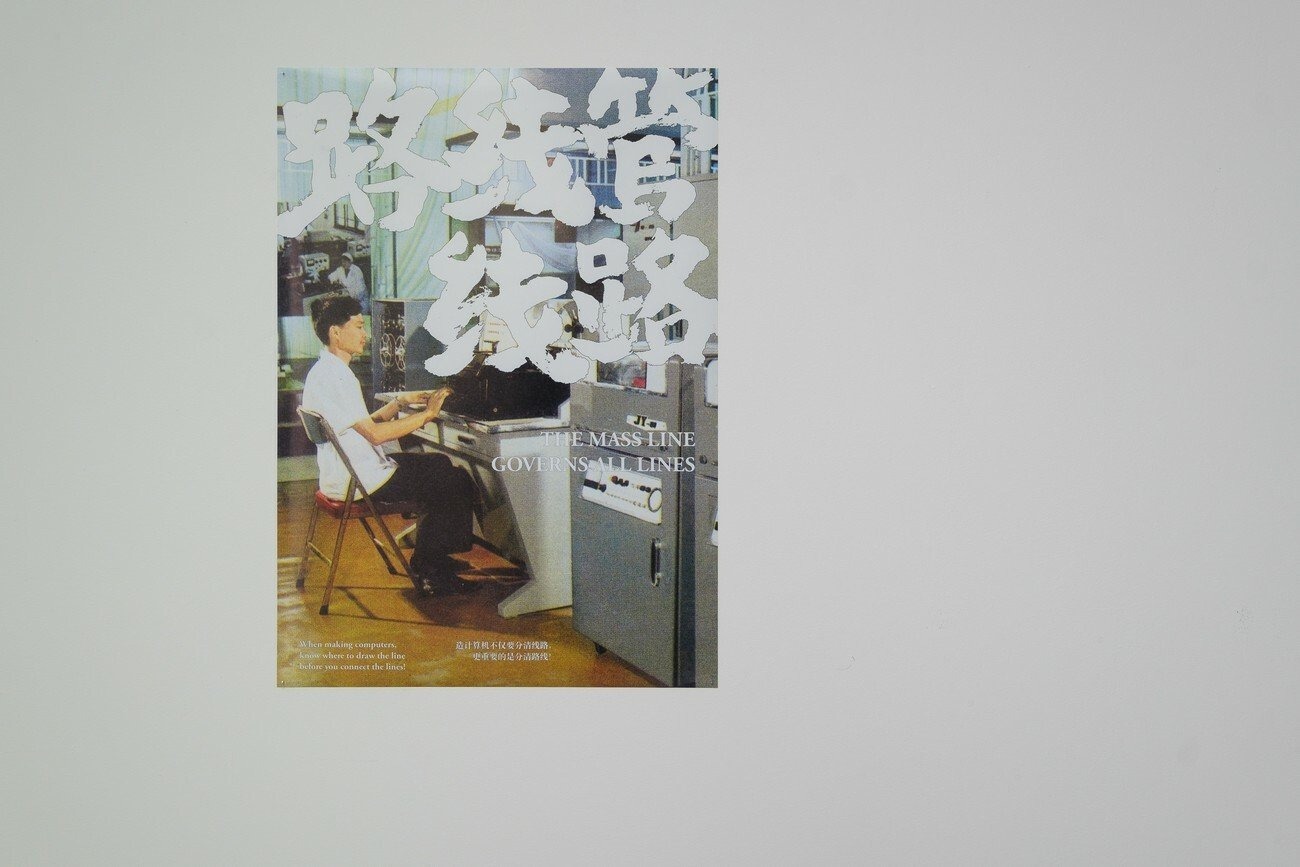

The key work in the exposition is the second chapter of an ongoing film project that maps the hundred-year history of the development of the textile industry and its many afterlives within the Greater China region. Each of the three chapters, namely Lineage, Lining, and Landing, is situated around a historical turning point and examines the shifts in the conditions of labour, capital, and technology as one socio-economic system gives way to another.

The second chapter, Lining, begins with the movement of Shanghai’s cotton mills to Hong Kong on the eve of the Communist takeover, and extends into the Reform era during which Hong Kong’s industrial base would in turn be displaced to the mainland, this time concentrated around the southern region of Guangdong. Weaving together archival material, interviews with former factory workers and managers, and observational footage shot between Hong Kong and Guangdong, the narrative describes the postindustrial turn of Hong Kong and how its relationship with Guangdong exemplifies the horizontal “lines” of connection within contemporary global capitalist networks.

There are two posters included in the installation. They draw upon imagery extracted from publicity materials of the China Import and Export Fair, also known as the Canton Fair, during the 1970s. As one of the few occasions where Chinese trade representatives met foreign businessmen, the fair was where one could observe the ideological shifts of the Party as it gradually transitioned to a market economy integrated within global flows of labour, capital, and technology. The somewhat ironic pairing of the images with a set of devised slogans invokes the depoliticisation of technology that occurred as a part of these shifts, while questioning whether technological flows can ever be extricated from the lines of ideology.

Agata Ingarden’s installation consists of architecture made out of windows, retrieved from an office building in Kyiv. Multiple types of objects appear in these forms such as wooden molds, bronze sculptures, textile suites of two designs, modified cycling shoes, and video screens. The room itself has been stripped from its white plasterboard and false ceiling, uncovering the ventilation system and the eclectic composition of the innards of the exhibition space. From in between the reflections of the kaleidoscopic, semi-transparent glass systems of elevators, corridors, and basements are revealed, constructing an emotional dimension that exists partly in reality and is partly accessible through video screens.

The wooden and bronze objects come from the form of a rescue dummy which is a mannequin used for water rescue training. The wooden molds are populated with 3D scanned tree mushrooms that usually grow parallel to the ground. Here, turning in all directions suddenly they indicate a different or changing point of gravity and at the same time mimic an imaginary system of internal organs. Bronze pieces, covered with red modelling wax on the outside, with polished insides and oxidized edges, resemble armour. Costumes are sewn together from many coatings with visible stitches. Playing with the idea of a mould, Ingarden introduces us to different sculptural shells, referring to the multiplicity of layers.

This setting introduces the audience to a game-like world. Dream House — an imaginary program generating a real-life simulation for a group of characters called Butterfly People who are supervised by characters called Emotional Police. Sometimes separate, sometimes merging as one character, the Butterfly People explore the boundaries of their bodies, emotional states and communication through dance and unorganised movement. On one hand, their efforts and energy fuel the entire program, and on the other become a form of revolt against generalised social norms and a way to free themselves from the system. The emotional dimension is a playground to explore the experience of becoming a “being”, or the idea of memory and constructing/recomposing identity as an individual and as a group.

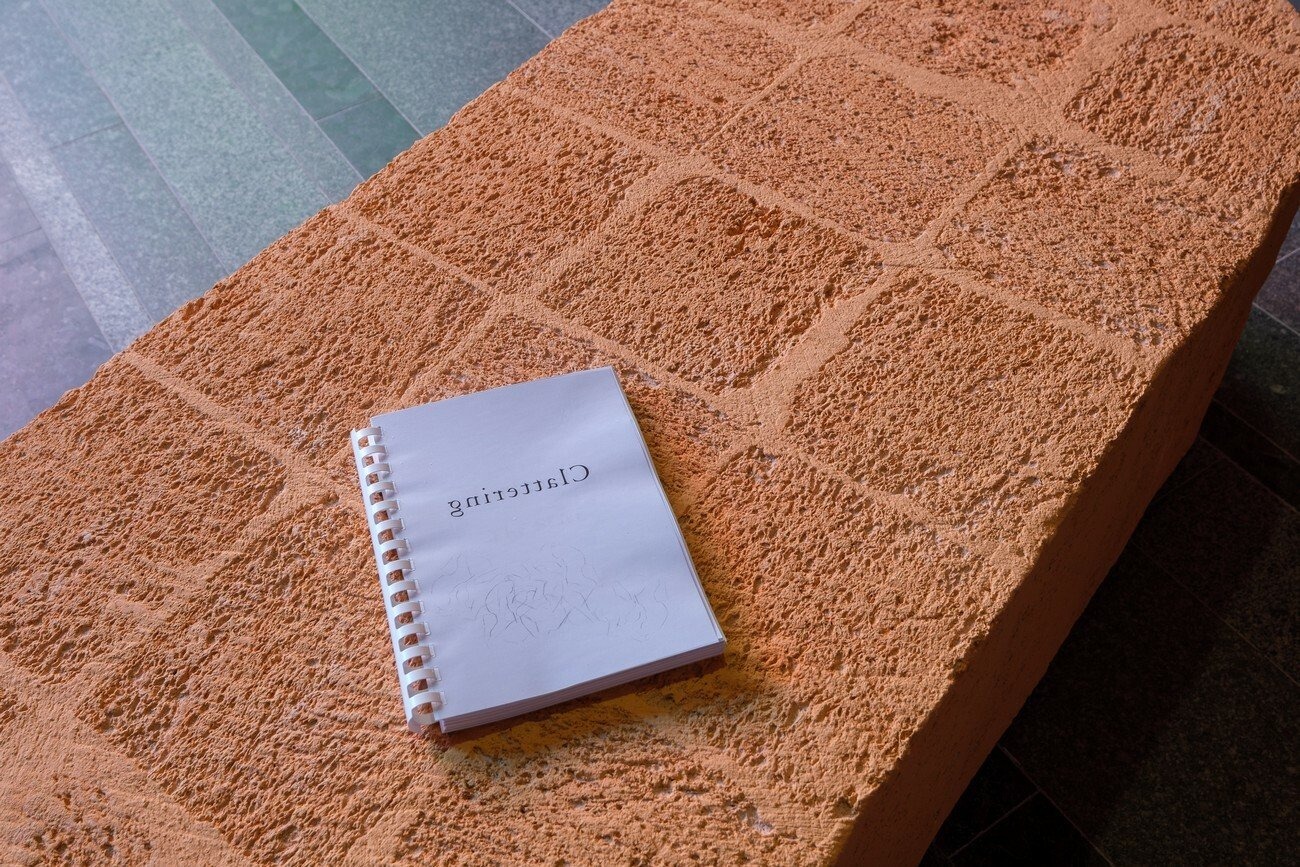

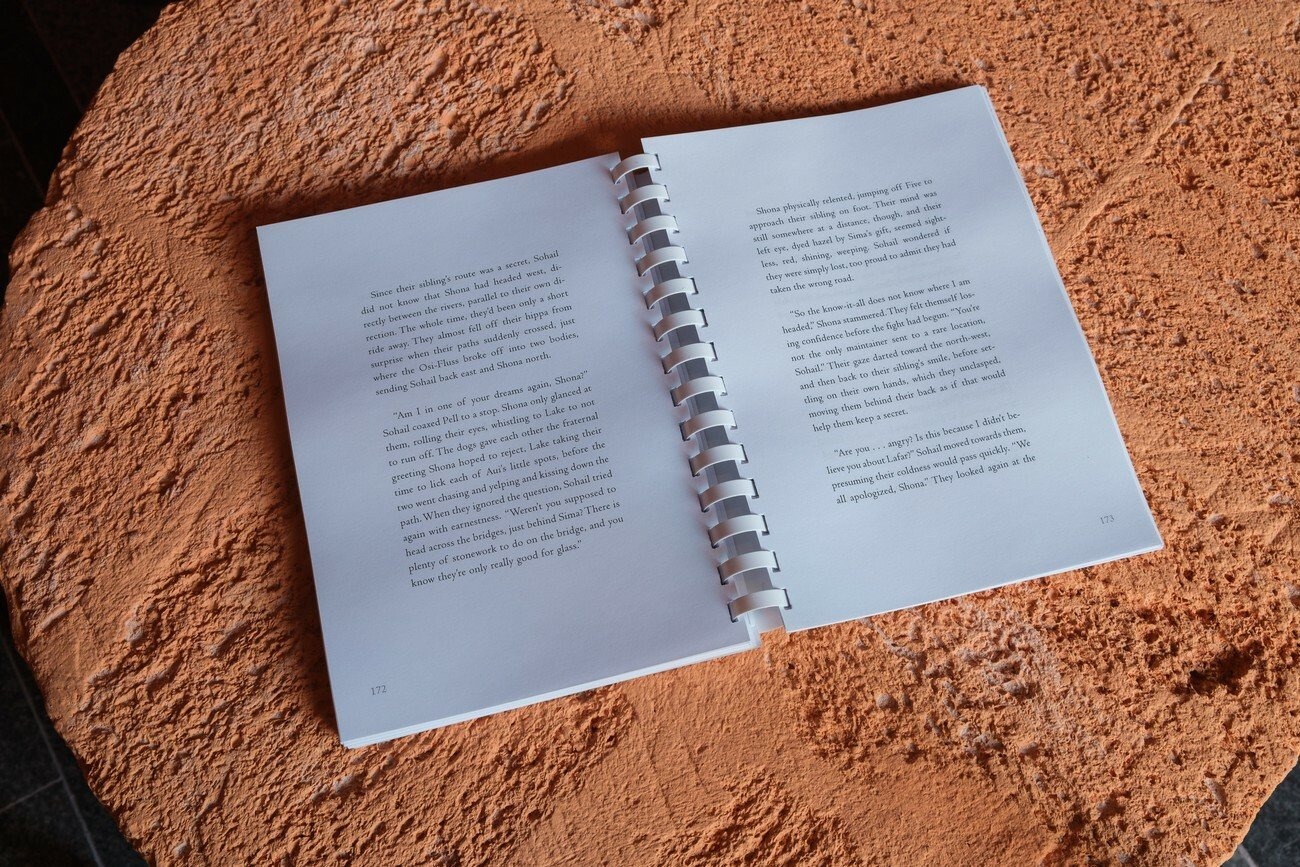

The installation emerges around a sci-fi novel called Clattering. The story, written in collaboration with writer Diana Hamilton, began as a proposition for open-mindedness, multiplicity, and opposition to the organizational states of our world, which is mostly built on various forms of dualism. Rindon Johnson’s practice is bound up with writing, which he scales up to spatial installations that contain various elements or media.

In the novel, Clattering, the authors question our accustomed perspective on relationships, hierarchical structures, reproductive systems, and resource control. Johnson and Hamilton ask these questions by creating subtle but important differences between humans and their human-like characters. The authors decided early on that in Clattering there would be no gender, no hunger, no war, no physical violence. Against this backdrop the conventions of our actual world look very different.

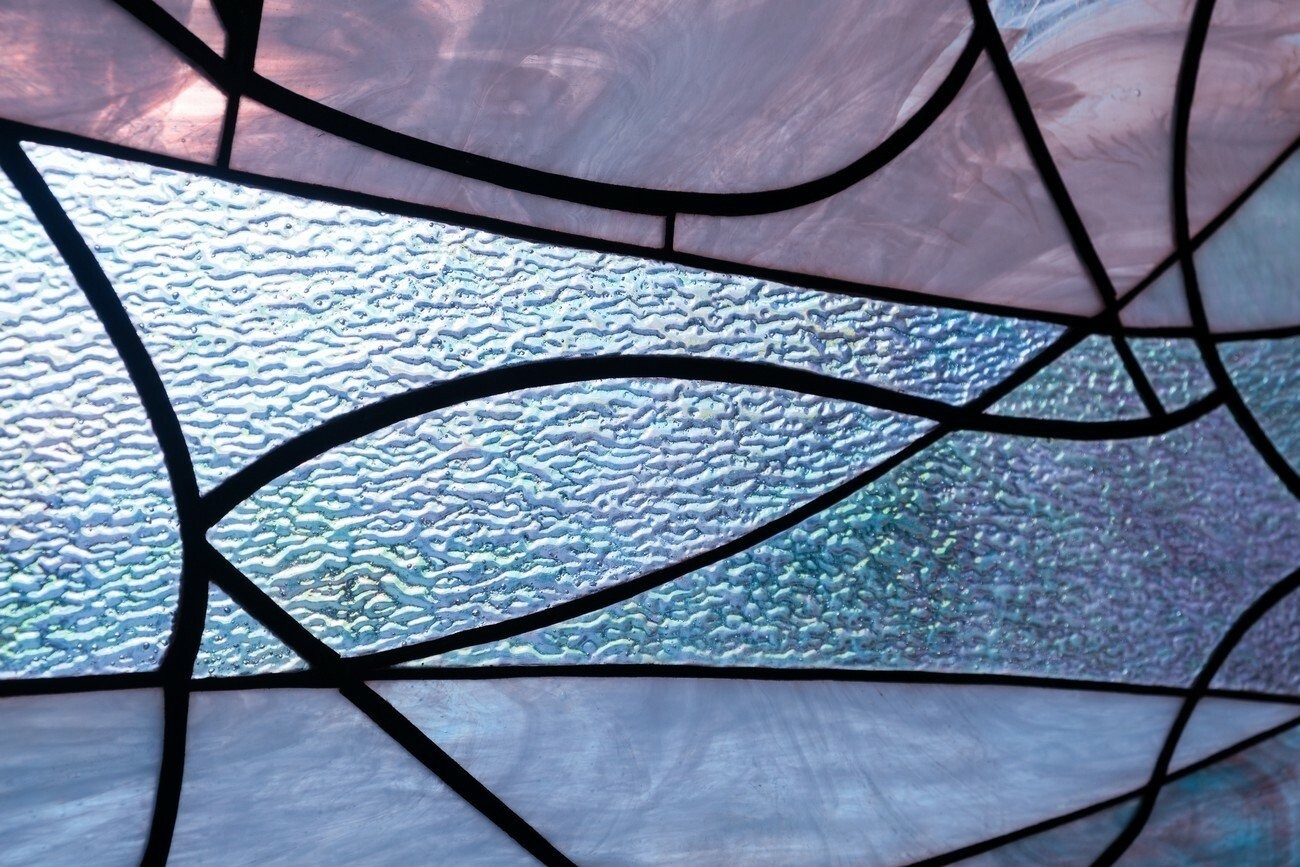

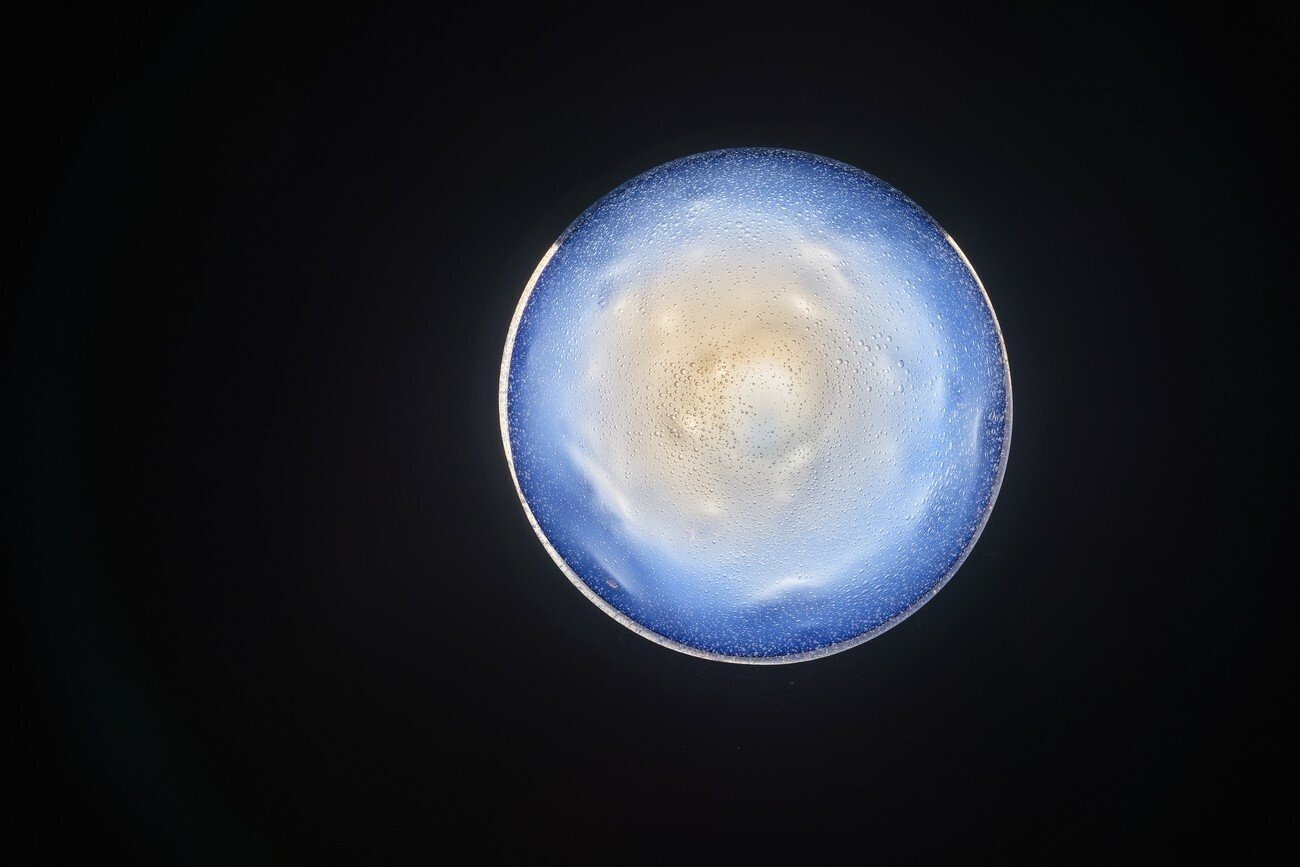

The story unfolds when the main characters of the book discover that the initial inhabitants of their planet were immortal until a certain knowledge was taken away from them. Among five protagonists only one enters the exhibition space, a glassmaker called Sima. A replica of Sima’s dream is seen as a central large-scale installation of an iridescent cloud depicted in stained glass. This visual experience brought them to the understanding that in one beam of light all colors exist at once. This comprehension suggests a perspective of inclusion and fullness.

The LED wall, which both opposes and illuminates the glass piece, shows the Bay of Jaffir, one part of the landscape of the video game version of Clattering. The video invites viewers to watch the shifts in light across the bay, through the trees, as the three planets move through the sky over the course of a day and a night.

Bronwyn Katz’s large-scale installation, /xabi, is an extension of a system of notation she has been developing to signify the phonetics of a creole language, which is typically made by mixing two different languages into a new one. Her iteration of creole gestures towards the Southern African click-based dialect of !Ora. The installation is manifested as a single, immersive environment. In it, a series of rock and steel sculptures — denoting the letters or symbols of Katz’s imagined language — are surrounded by what she identifies as curtains of rain, materialised as lengths of copper coated carbon steel joined together with hemp twine.

The rock and steel “letters” reference the forms found at Driekopseiland, a site of rock engravings with which the artist has been working over the last 5 years. The site is located along the Riet river in the Northern Cape of South Africa, originally known as the Gama-!ab, a !Ora name meaning “muddy”. The petroglyphs of Driekopseiland are covered by the waters of Gama-!ab in the rainy season and exposed during the summer drought. Katz is interested in this collaborative intervention of water in the creation of signs, symbols, and language.

Elaborating on the generative and healing possibilities of moving water, the installation includes a sound recording of the artist moving salt water around in her mouth following the extraction of her tooth. Resonating throughout the space, the sound creates an awareness of the connection between earth and body — both living entities marked with scars and memory. The title, /xabi, is a !Ora word that can be translated as a spurt of water from the mouth, and Katz is invested in the potential of the action suggested by this word. With this installation, she posits that language, and its close relationship to the natural world, as a tool for the care of the self, and, by extension, the community and the earth.

Lap-See Lam employs VR technology, 3D scanning and animation to explore the history of the Cantonese diaspora in Sweden. Her main subjects are Chinese restaurants in Stockholm, their interior aesthetics and cultural codes. Via these establishments Lam considers the role that such specific sites have on the construction of the identity, as well as the history and heritage of a particular local community. She intertwines fictional narratives in complex immersive installations, combining sculpture ensembles with poetic stories in virtual reality.

In her expanded narrative, Lap-See Lam presents her ongoing project Phantom Banquet, based on the story of a young waitress who disappears through a mirror and into another dimension in 1978 in Stockholm. The installation is divided into several chapters. The viewer’s journey begins in the remnants of a dining room of a now-defunct restaurant.The tables and chairs have become digital ruins, reduced to a blurry illusion.

The following space is illuminated by the neon sculpture of a ghost — a form generated by the moving figures accidentally captured by Lam’s 3D scanner in the restaurant. Its figure appears as an ancestor and a guide to the banquet room around the corner. The closed and intimate space with a round table in the centre brings to mind a spiritualistic seance. Through VR headsets the visitors are transported into another dimension, where, together with a mysterious guide, they cross over the dark universe of restaurants that once existed, a space that expands over the course of the trip.

The paper sculptures presented in the space are part of an upcoming project that continues where the story of Phantom Banquet ends. They belong to the character Singing Chef, and each paper suit is named after the place from which its shadow motifs are collected.

By making possible a space of shared collective memory and experience, Lap-See Lam creates a sensitive anthropological study on the notions of heritage, metaphysics, technologies, and otherness.

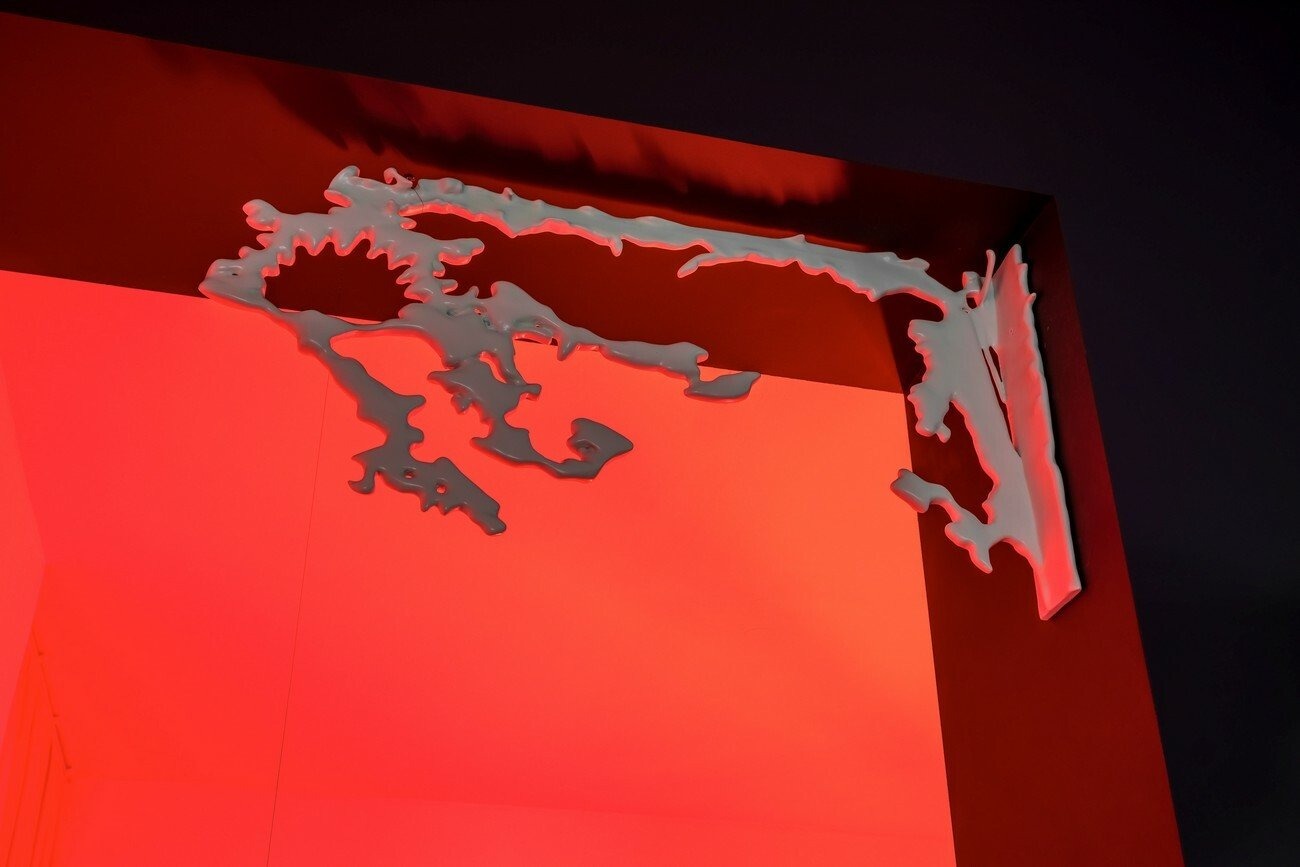

For her installation, Mire Lee creates an architectural interior made of formworks — typical tools for modeling building facades. The molds are removed after the material inside dries and are then reused over and over again. In a sense, these formworks “give birth” to concrete blocks, a process in which their surfaces appear to carry the traces of all the produced modules. The structure can be entered, allowing the viewer to walk through its inner architecture. Being inside of this half-closed space we find ourselves surrounded by walls, confined by formwork skin.

From here, the structure can be navigated as if it is an internal space of a body: there are two organ spaces and vessels that connect them. In the adjacent symmetric formwork rooms, there are constantly working peristaltic pumps. The sculptures on the top of the machines are entangled, creating a hybrid body. The physical feeling of outside and inside becomes blurred in all elements of Lee’s installation. The dry and hard facade surface is covered with concrete, while the outer layer of the sculptures are cracked allowing a viscous liquid to flow out. The slush inside bursts through a shell that once looked solid.

The materiality and movement of the sculptures directly targets our more tactile senses. Thus, the possibility of interpretation goes beyond a verbal means of communication, becoming the work’s foundational sinew. When language as a means supersedes human understanding, certain uncomfortable emotions become aesthetic experiences that can then be shared in common.

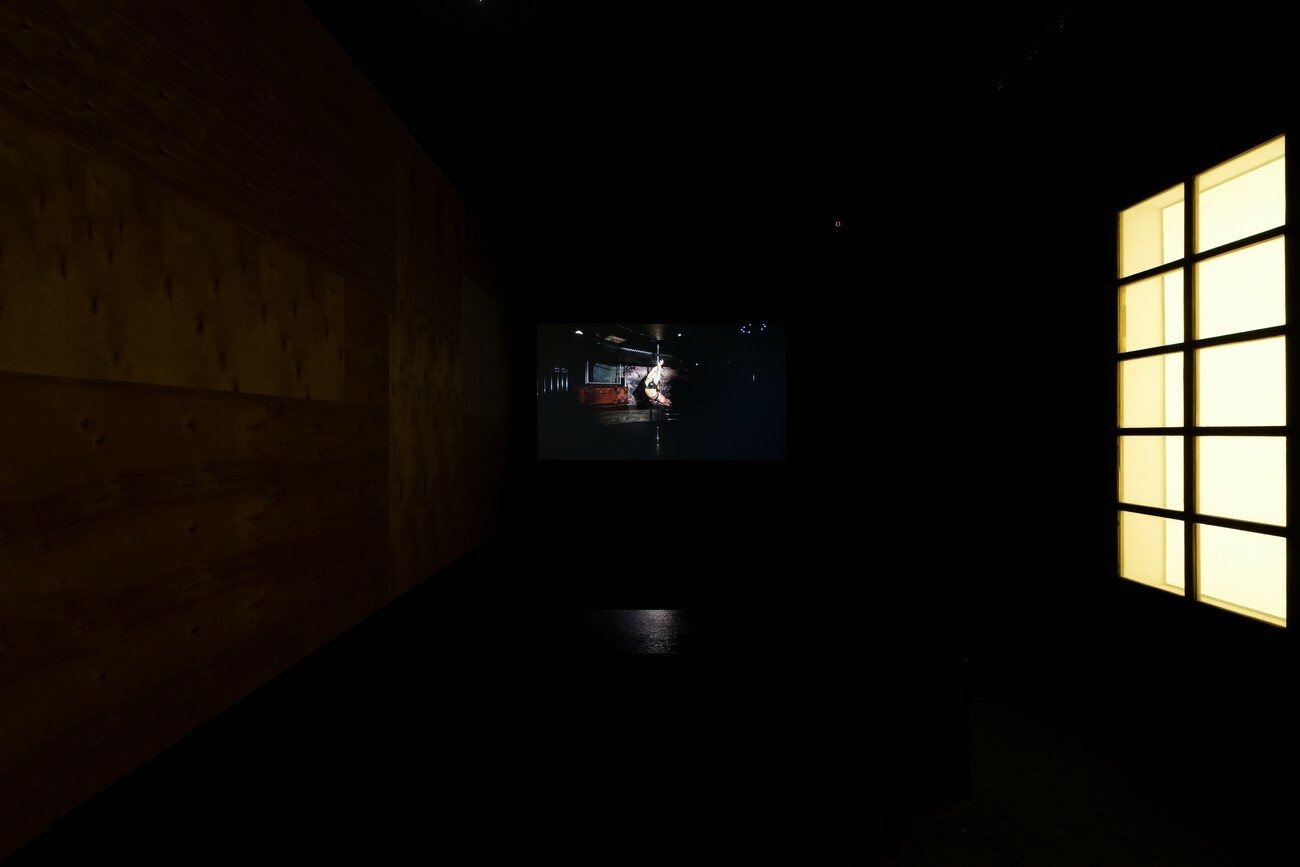

This installation represents a cohesive body of work centered around the question of visibility and invisibility. Each compositional element of the work has the potential to affect our physical experience of the space; of what we can see, hear, or feel. Everything here moves or alludes to movement, such as the use of a chemical reaction to form spontaneous images on copper, or the deep bass frequencies travelling through our bodies.

For this work, Paul Maheke takes radio astronomy, a field of study in which vision is only a secondary sense in the discovery of our galaxy, as a point of entry in order to further interrogate our earthly experience of the cosmos. Each planet emits sound: a song specific to each one of them. The frequencies emitted by the electromagnetic fields of planets, stars, and pulsars have been instrumental in the development of radio astronomy.

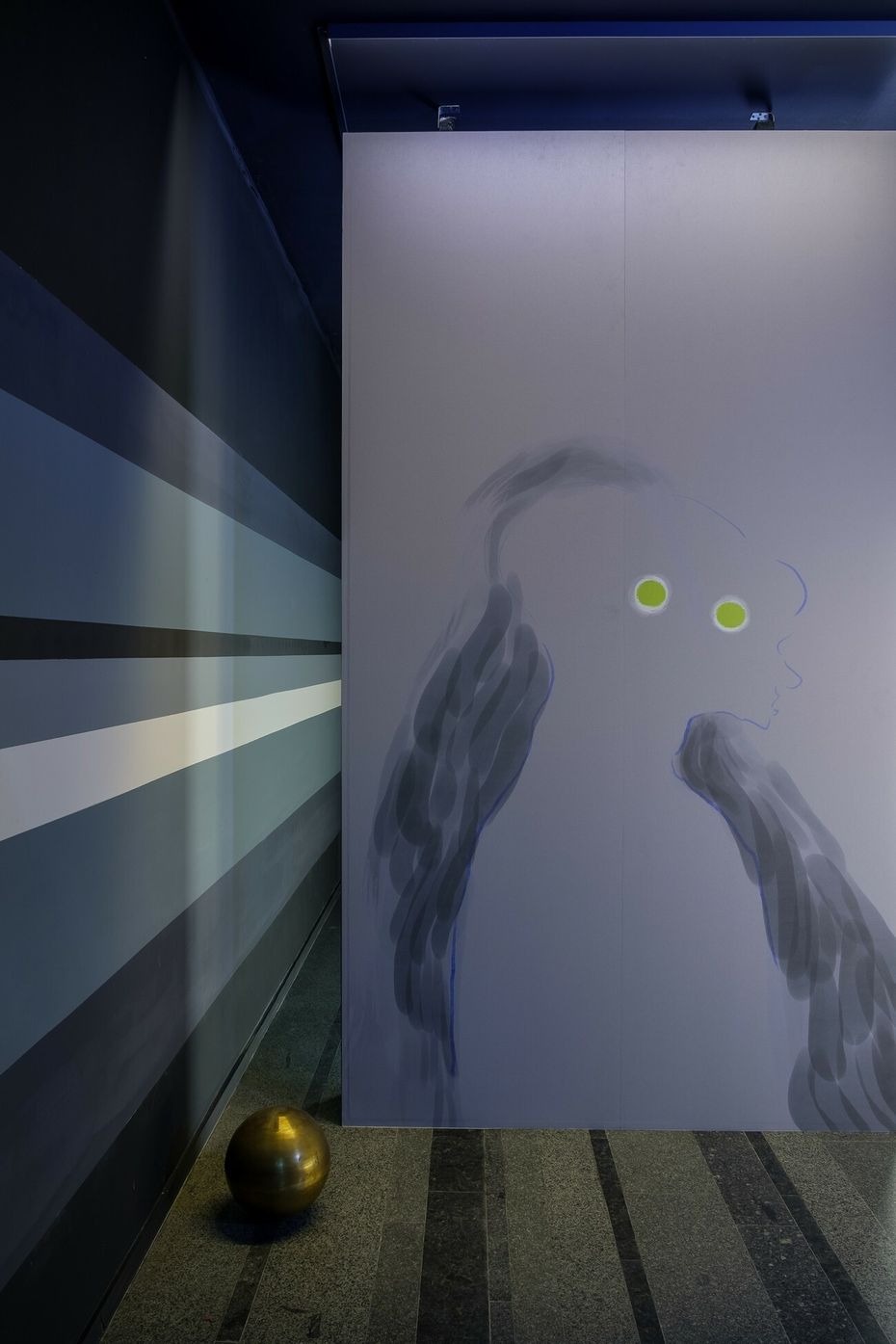

In When the bodies dissolved into the ether, orbs sang notes of the heavens, Maheke plays with the poetics of a body dancing to the sound of the Moon. This video diptych, projected on two identical screens erected in two consecutive rooms, uses motifs of presence and withdrawal. Both screens are made from HoloGauze, a material known for producing the illusion of a hologram. Captured on camera and shown as a video loop, the performance encompasses different choreographic moments based on principles of circularity and renewal found in the cosmology of ancient Congo, as well as in French Créole poet Edouard Glissant’s writing.

While a dancing figure appears and disappears repeatedly on screen, words are mumbled, a couple of wall drawings depict ghostly beings and metallic planets punctuate our journey through this sensorial space, which has no beginning and no end. Combining sound, light, and movement, the installation exists mostly as an attempt to blur the field of vision by arguing for the presence of that which is (made) invisible.

The spatial installation Can’t take my eyes off you discovers the prospect of having children as well as the choice of not giving birth. It is inspired by the David Cronenberg horror movie The Brood. A grotesque picture of motherhood narrates the story of a woman who, as a result of a psychoplasmic therapy, brings to life a number of mutant children, who then roam the town killing everyone who has ever hurt their “mother”.

Mental health is among the essential issues raised by the work. Constantly feeling pressured in conversations about motherhood, the artist critiques society’s treatment of those who decide to remain childfree. Mendick uses her personal story to open up a wider dialogue. In this case, conversation about the psychological impact of reproductive pressures engages both her own obsessive thoughts and the belief that an individual voice can bring change to the customary treatment of women.

Lindsey Mendick’s installation utilizes cinematic techniques drawn from the horror genre. She creates an installation divided into two settings; the first one represents an outdoor space with a playground, idyllic blue skies, and fake-grass underfoot. The second room reproduces a perfectly typical interior of a1970s house. Both spaces are inhabited by bizarre celeriac-headed infants who evoke a pervasive feeling of anxiety. These ceramic children are frozen in all manner of dangerous and terrified moments, showing the hostility of the environment and the impossibility of constantly monitoring their actions.

In the final space, there is a TV playing a video which combines cartoon footage with Mendick’s voice singing a lullaby-like interpretation of the song Can’t take my eyes off you.

In her works, Henrike Naumann investigates the consequences of the unification of East and West Germany in 1990 and the influence it has had on the further development of German society and its identity. She creates compound installations of furniture and home decor that explore social and political problems on the level of interior design, revealing the connection between personal aesthetic preferences and radicalized political beliefs.

For the Future Generation Art Prize 2021 Naumann presents her work 2000, which takes the year of the new millennium as the starting point for a discussion about the post-unification period and the influence of postmodern design in Germany. The installation consists of furniture pieces, design objects, and artifacts of that time, sourced from the artist’s personal archive, Expo 2000 in Hanover, and the living rooms of Mönchengladbach. Together they represent the postmodern era, and, arranged based on the artist’s research on social media, composite images of apartment interiors of East German neo-Nazis. The grey carpet on the floor duplicates Germany’s territory borders, depicting the East and West parts as two separated sections. Through the practice of reconstruction, Naumann seeks to define the reasons why these aesthetic codes are still common in German homes and how they affect the future of the country.

The films Triangular Stories (Amnesia) and Triangular Stories (Terror), integrated into the installation, tell the story of two different groups of young people. While teenagers from West Germany look forward to a party at a club called Amnesia in Ibiza, their peers from East Germany become violent and aggressive under the influence of neo-fascist ideology.

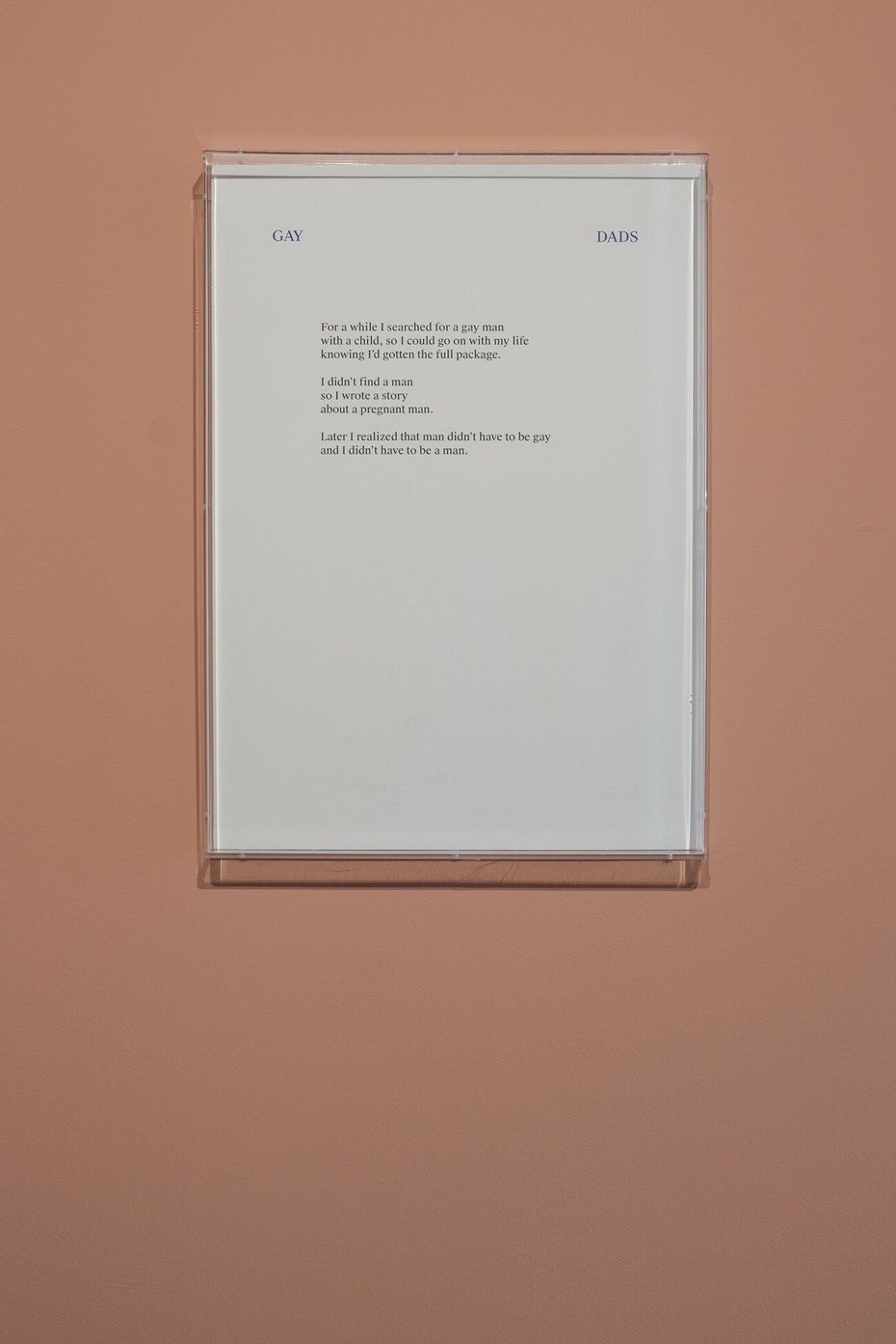

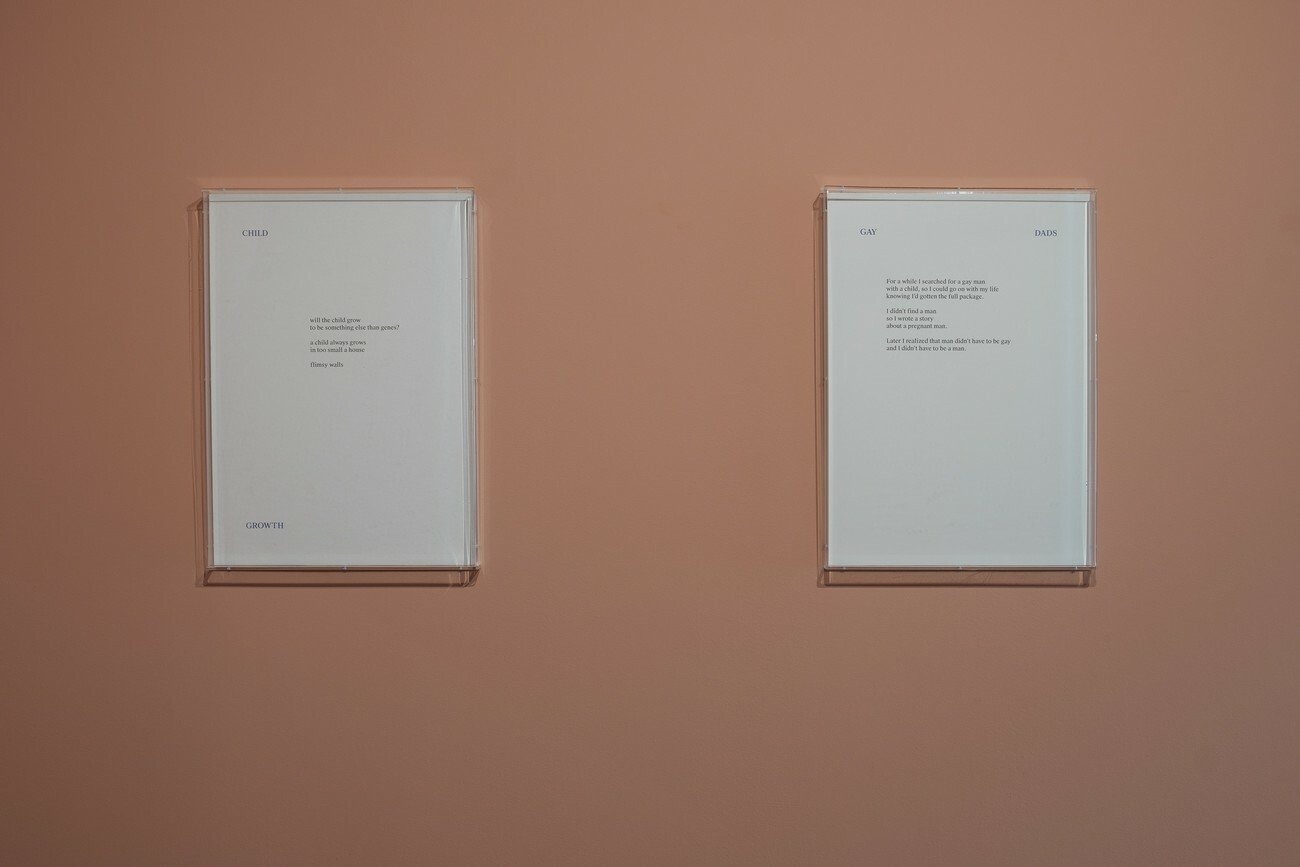

Middle Ages is short fiction film that focuses on a group of friends and lovers facing a crisis about their sexuality and desire for reproduction. It tells the story of a heterosexual couple struggling with infertility issues (Mirene and André), while a homosexual couple (Carl and Vicente) also try to have a biological child using an experimental technique that falsifies gestation by implanting an ovary in a male cis body. The classic cinematography, anchored on the performance of the cast, which includes the artist, is contrasted with an almost science fiction narrative.

As in previous films by Neves Marques, the contrast between image and speculation produces a feeling of estrangement and serves as a backdrop for the exploration of interpersonal dramas in a rapidly accelerating world, as well as political inquiries into gender and sex, the coloniality of technology and science, the ecologically natural and the artificial, and a break with expected roles. In fact, the story comes from Neves Marques own experience, circle of friends, and conversations about reproductive desires within a LGBTQI+ context.

As such, the film’s title, Middle Ages, refers to more than the characters’ moment in life, a period during which the issue of reproduction, whether desired or not, becomes increasingly present. The title also works as an image to provoke thought about an era of transition, where established rules, conceptions of the body and gender, beliefs and technology, begin to shift and become more fluid and politically unpredictable.

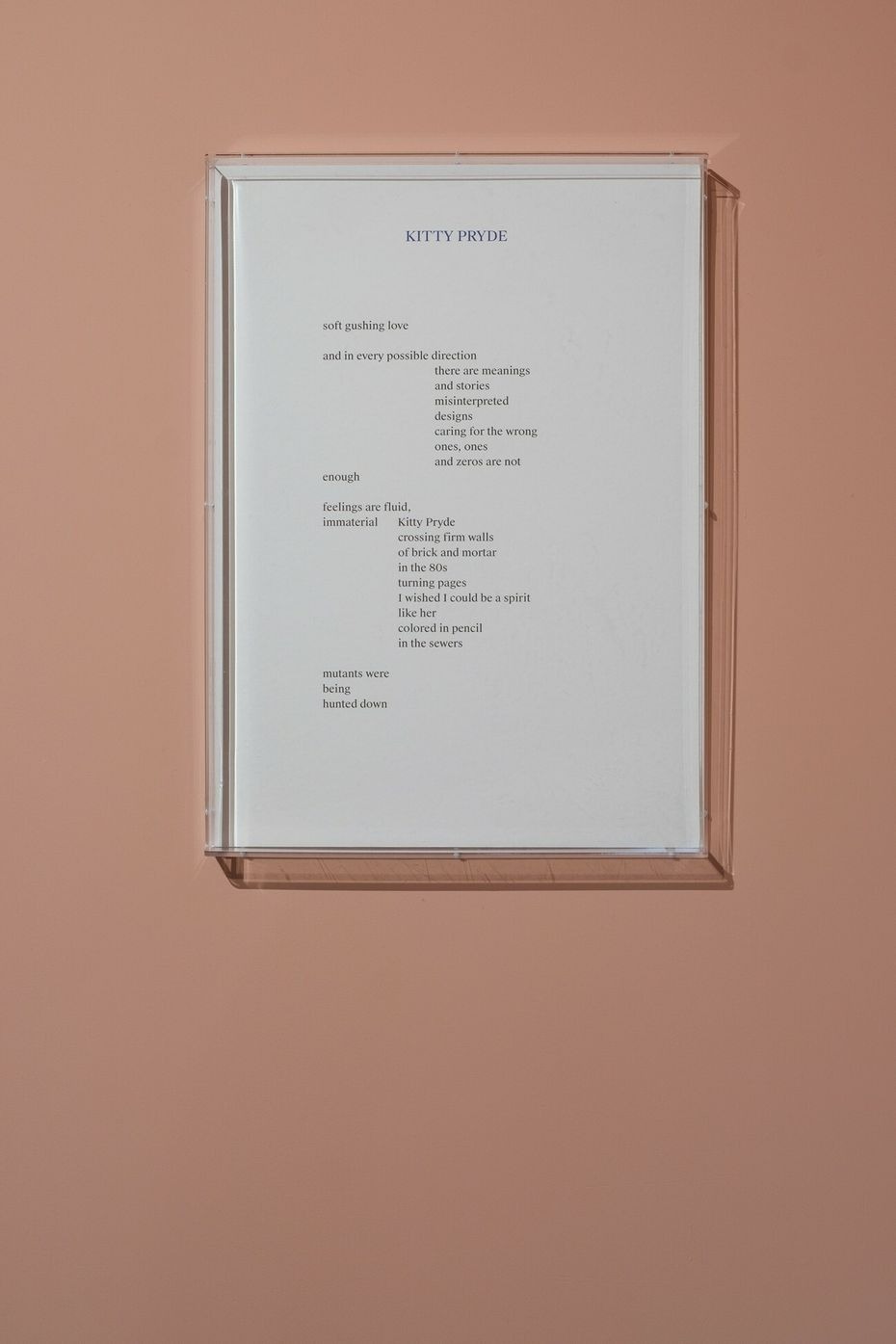

Though not a series, the exhibited poems each reflect and are built on fragility, intimacy, and exposure. As a growing practice of Neves Marques, their poetry navigates the thin line between reality and fiction, autobiography and speculation, the experiences that belong to the artist and to the people who surround them. Expressing in subtle ways the daily trappings of normativity and how they clash with the fluidity of bodies and dysphorias, they also touch upon the influence of science, technology, and popular culture on the imagination.

Using found photographs and archival materials as a source, Frida Orupabo creates multiple collages that investigate themes of race, gender, identity, sexuality, and post-colonialism. Mainly rendered in black and white, the depicted figures and objects remain minimalistic, visually clear, and open to interpretation. The artist’s central focus is the construct of a black female body — she investigates the ways it is presented and perceived through historical narratives, popular culture, and media. The work explores the ability of the gaze, which translates relations of power, to determine the way people see and interpret different social and political issues.

For her work Two Women, Frida Orupabo creates a complex collage. It implies everyday changes to the element’s placement, and therefore becomes a subtle performative action in the space. Each compilation of the objects produces new meanings and narratives, giving the viewer a sense of their own ability to change the flow of the story.

The relationship between the pictures of the black and white women becomes defining in the work. Responding to the claim of American author and feminist Bell Hooks that the white feminist movement made “woman” synonymous with the white woman and “black” synonymous with the black man, the artist seeks to restore the visibility of the black woman. Her figure in the installation cannot be removed, thus preserving the possibility of her perspective and view. At the same time, however, in all possible scenarios she is positioned together with the image of the white woman, thus remaining partially covered.

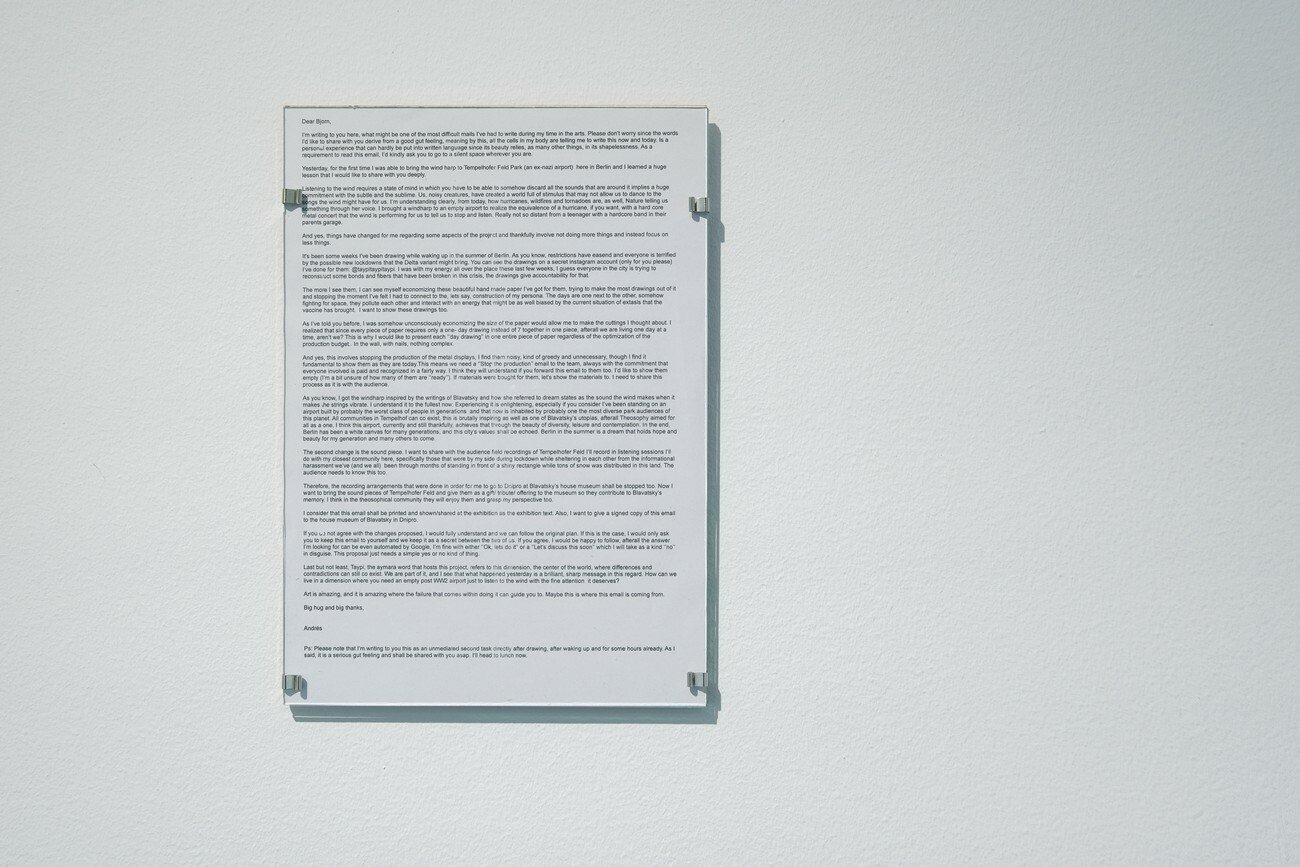

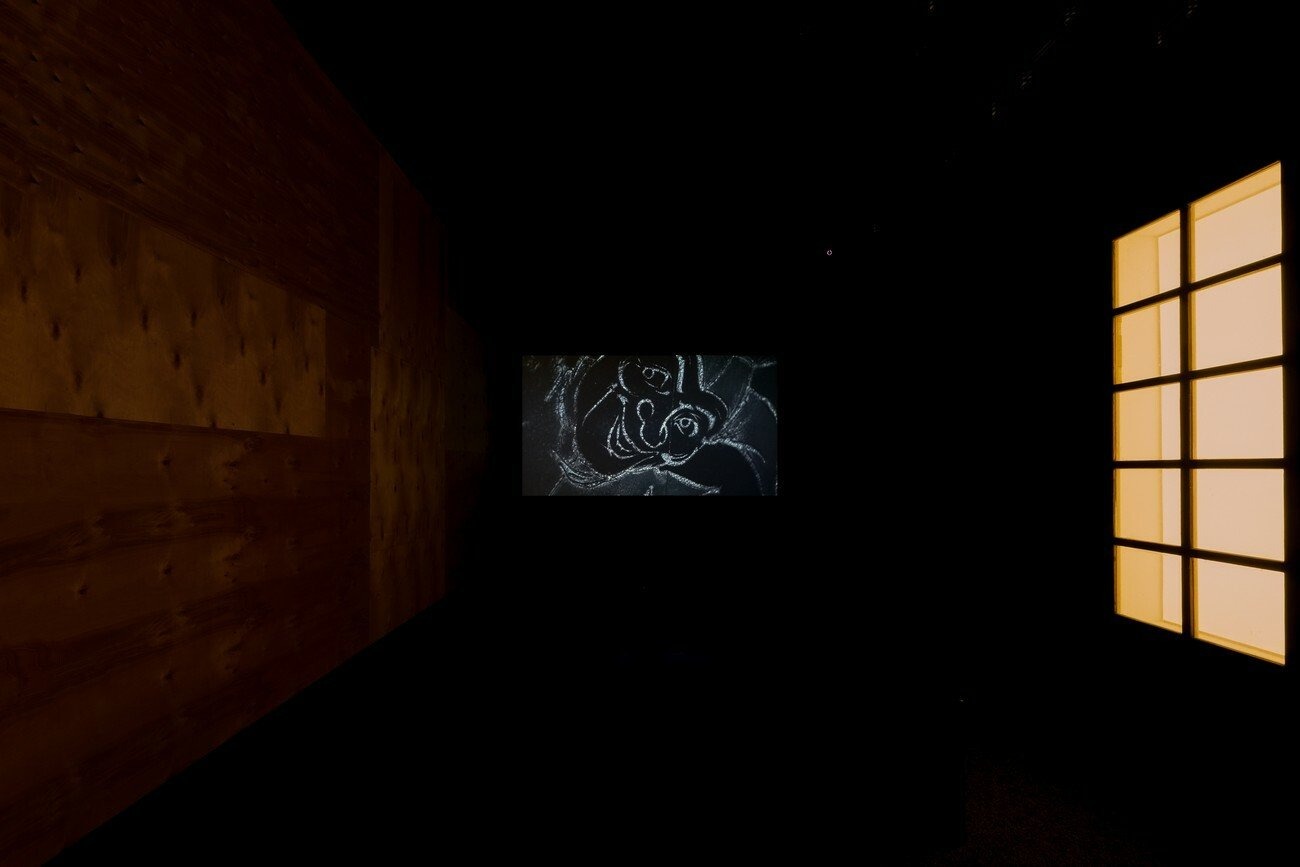

In his recent works, Andres Pereira Paz is interested in the ways in which identity is constructed, and how the flow of relationships, life experiences, and narratives influence its constant shifts.

The title of his new work Taypi, presented within the Future Generation Art Prize 2021, refers to a word in Aymara, a language of the artist’s native country of Bolivia. Its meaning can be interpreted as “in the middle of” — a point or a dimension in space where the dialogue between different and even antagonistic energies takes place, composing a universal space.

This dichotomy is revealed in drawings made as the artist’s first waking act in the morning, still in transition between dreams and life. What determines our consciousness in this fragile borderline state? How soon do we overtake our identity and become ourselves? The drawing process takes the form of a surrealist exercise that tries to portray the condition between sleep and wakefulness regardless of its content. Considering these drawings as the result of dreams, and as a research experience, Pereira Paz explores the state of mind behind waking up as an essential part of the day where identity and personality are negotiated.

A sound piece, echoing in the space, presents recordings made by a wind harp that was specially produced for the project. It is capturing the moments of silence and sound, vibrance and resonance in Tempelhofer Feld, from the window of the artist’s bedroom and near the canal close to his apartment. Both elements — drawings and sound — dance together in a state of randomness that includes the potential of learning such a state brings.

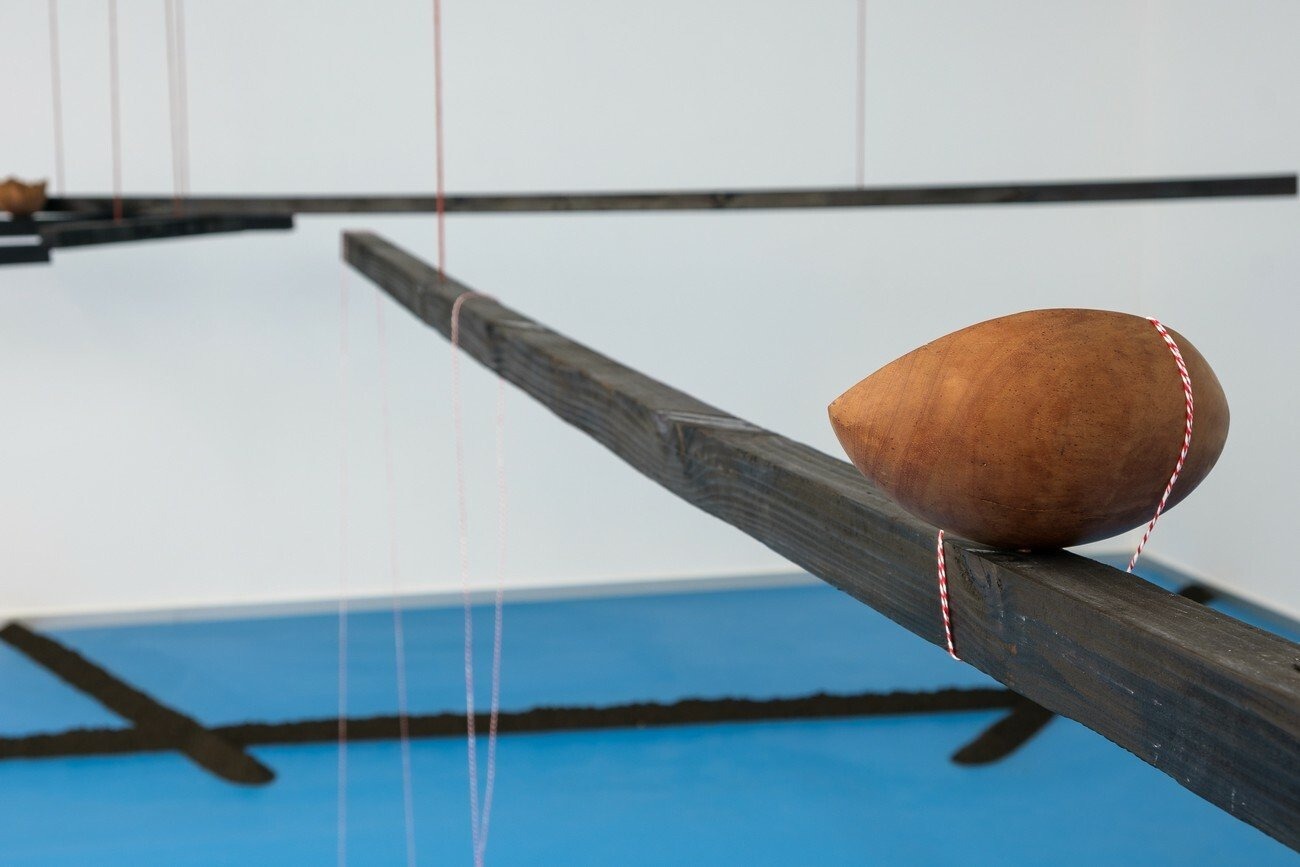

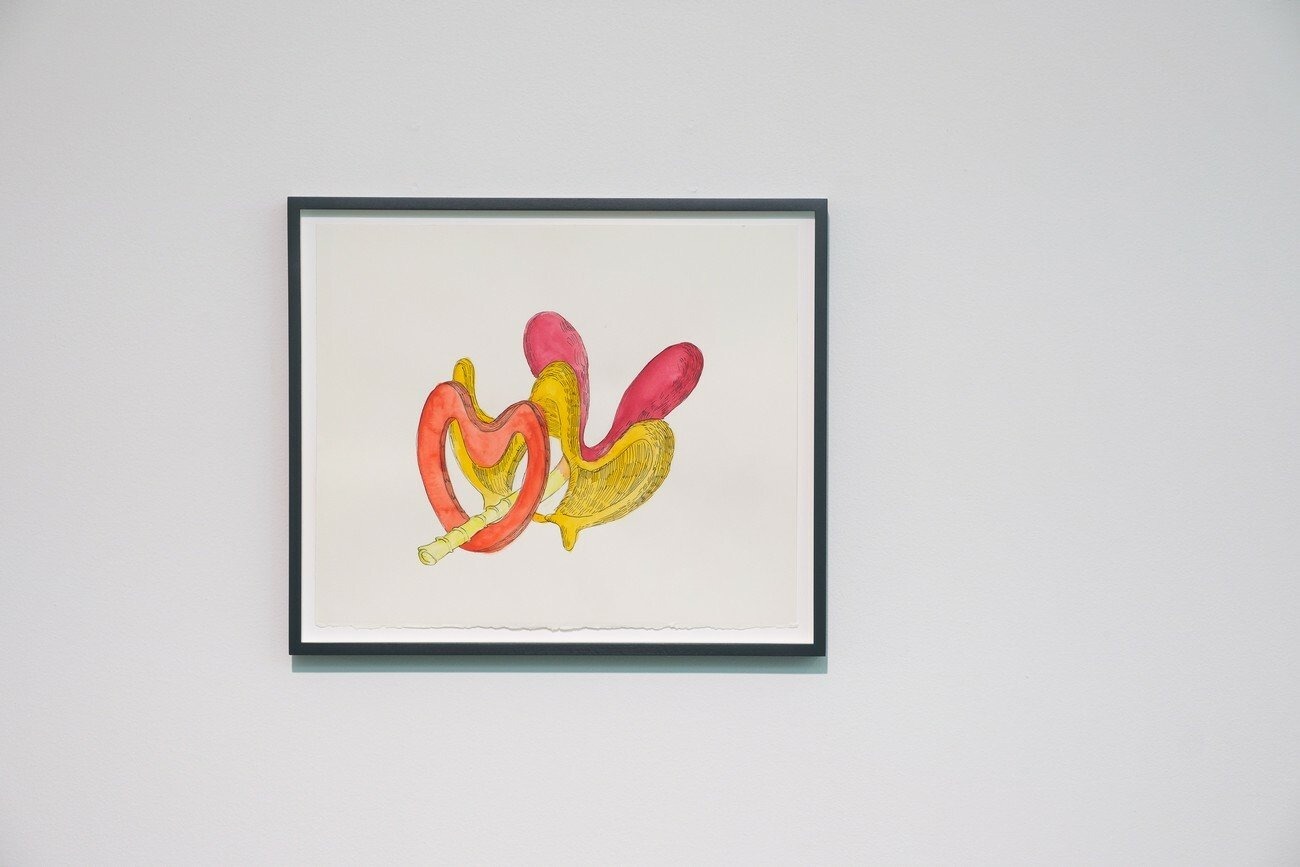

In recent years, Teresa Solar has developed large-format installations in which families of sister sculptures vary in shape and size, creating complex ecosystems of thought. She explores concepts such as insulation and immunity and develops them through a multidisciplinary production mainly focused on sculpture and drawing. Throat, pore, hatch, tongue, pipe — her pieces are populated with connotations of connectivity and flow and based on the creation of multi-layered narratives.

In Amplified wind pattern the artist draws a parallel between bones — as hollowed structures, carriers of tissues, veins and cell communities, message pathways — and kayaks and flutes. The first ones being primitive vehicles of migration, and the second ones connectors of bodies and knowledge. Both of them hollowed and traversed by the wind, both of them emitting an air signal that evokes body fragility over the sea while simultaneously celebrating the human capacity for transition and transformation.

The artist works with pieces that vary in size and materiality: clay, found objects and human symbols coexist in her work. Teresa Solar approaches these relationships from an organic sensibility, as if they were bodily functions, but she also accentuates the complex system of relationships in the industrial world, where hybrid forms of existence that combine organic and synthetic properties are constantly being produced. In Hermaphrodite Solar evokes a not yet fully developed reproductive organ that has been unearthed from the ground and exposed to the public. In contrast to the raw organic exteriors, the interiors are delicately finished and clad in bright colors reminiscent of miners’ overalls or sprays used to mark new tunnels in the underground darkness.

Trevor Yeung creates a site-specific installation, presenting two different works. Mr. Cuddles shows the Pachira-trees hanging from the ceiling by colored straps. Night Mushroom Colon is a smaller-scale object made of several plug adaptors with glowing mushrooms. Working spatially, Yeung combines and contrasts tall suspended plants with a tiny plug-in night light at floor level. The human scale here is a crucial aspect that becomes an opportunity for the audience to feel themselves as a part of the installation and to match the different measurement systems.

Initially created in 2018, when a “super typhoon” was passing directly over Hong Kong, Mr. Cuddles obtains an additional layer of connotation during the period of the global pandemic. The trees which, throughout the duration of the exhibition, are forced to grow confined in unhealthy proximity to one another become a metaphor for society at large, as the experience of cohabitation has become marked by inescapable interactions. Trevor Yeung’s work speaks about the different kinds of relationships formed within small groups and challenges the experience of a shared dwelling.

In contrast, Night Mushroom Colon becomes a specific gesture of care. Alone at night, a person switches on a lamp which somehow becomes a companion. The slight bioluminescent glow of the mushrooms produced by an electrical converter reminds us about non-human presence and the agency of multiple species.

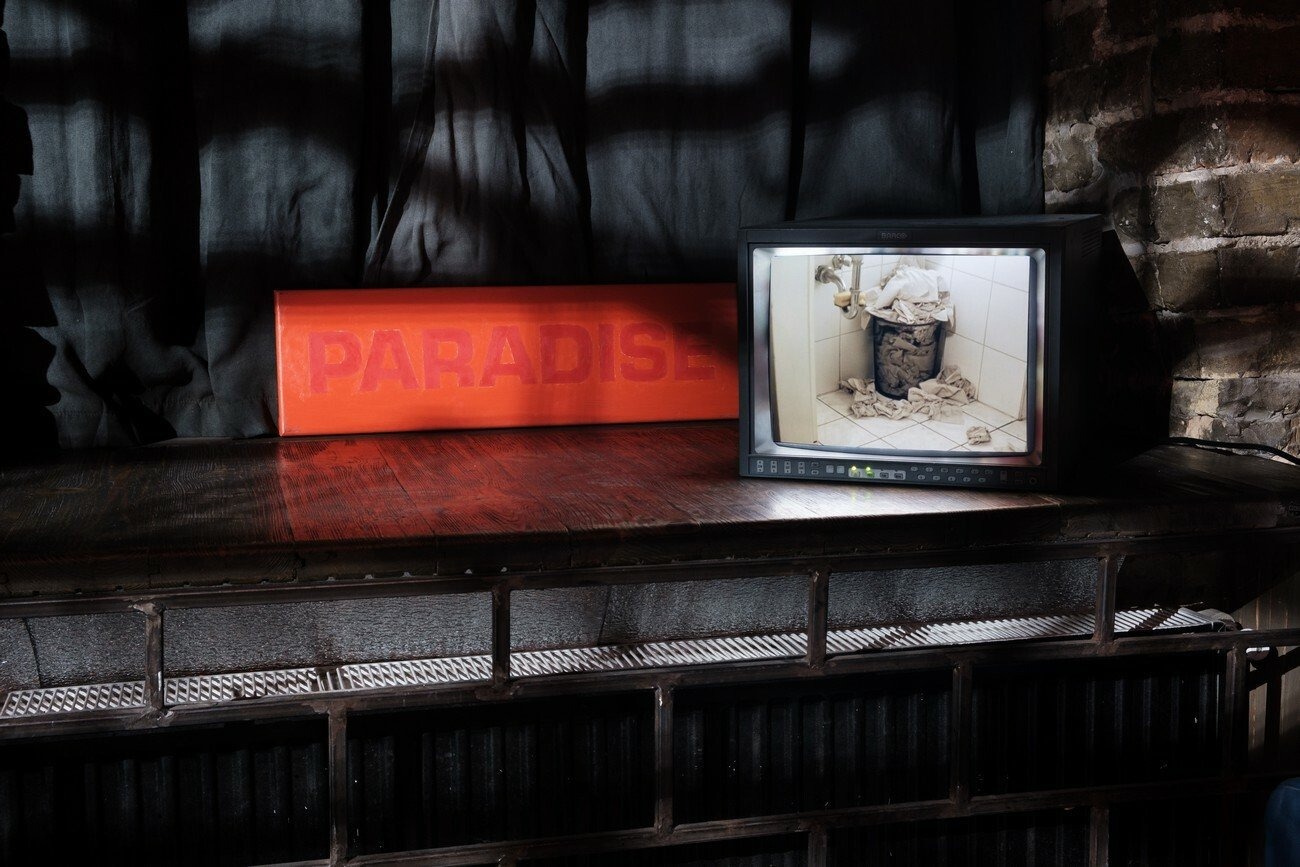

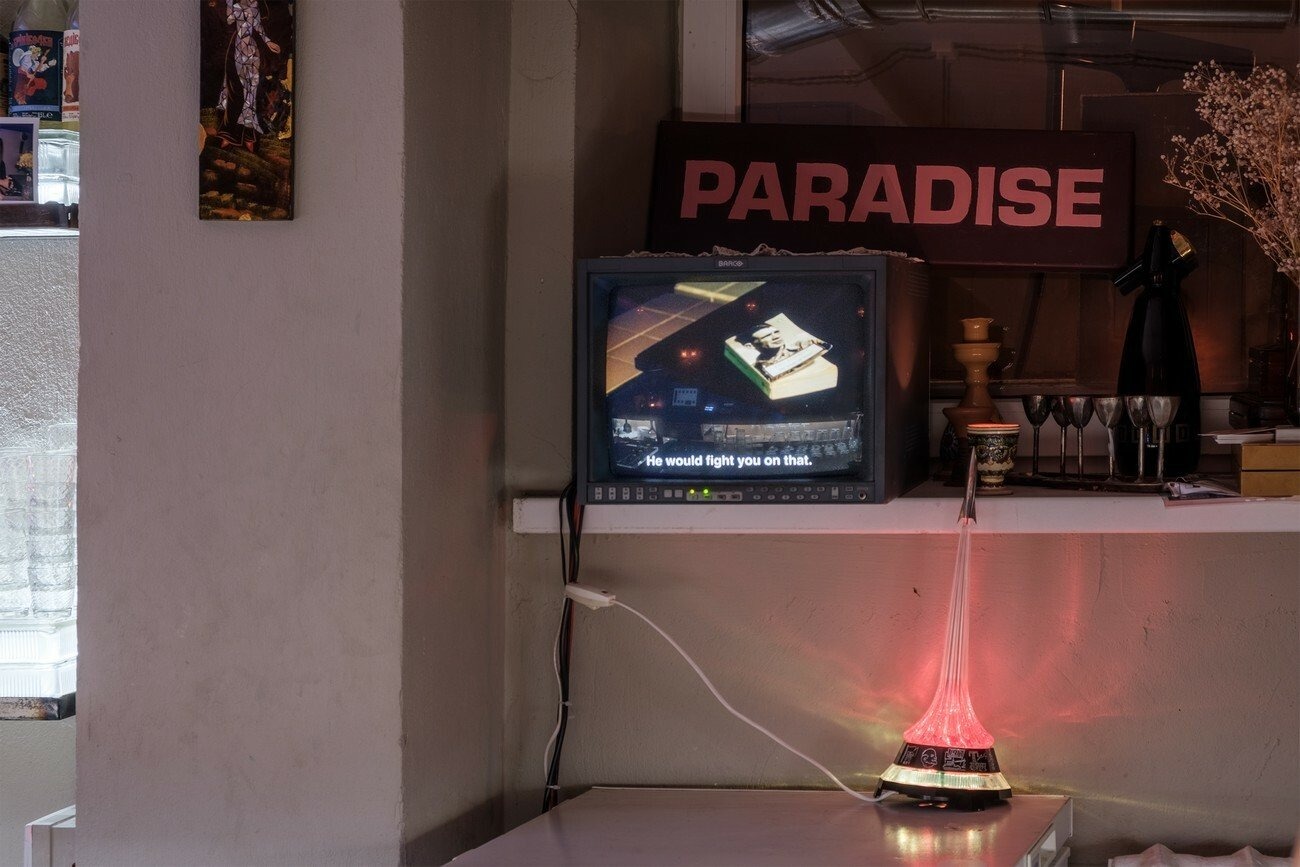

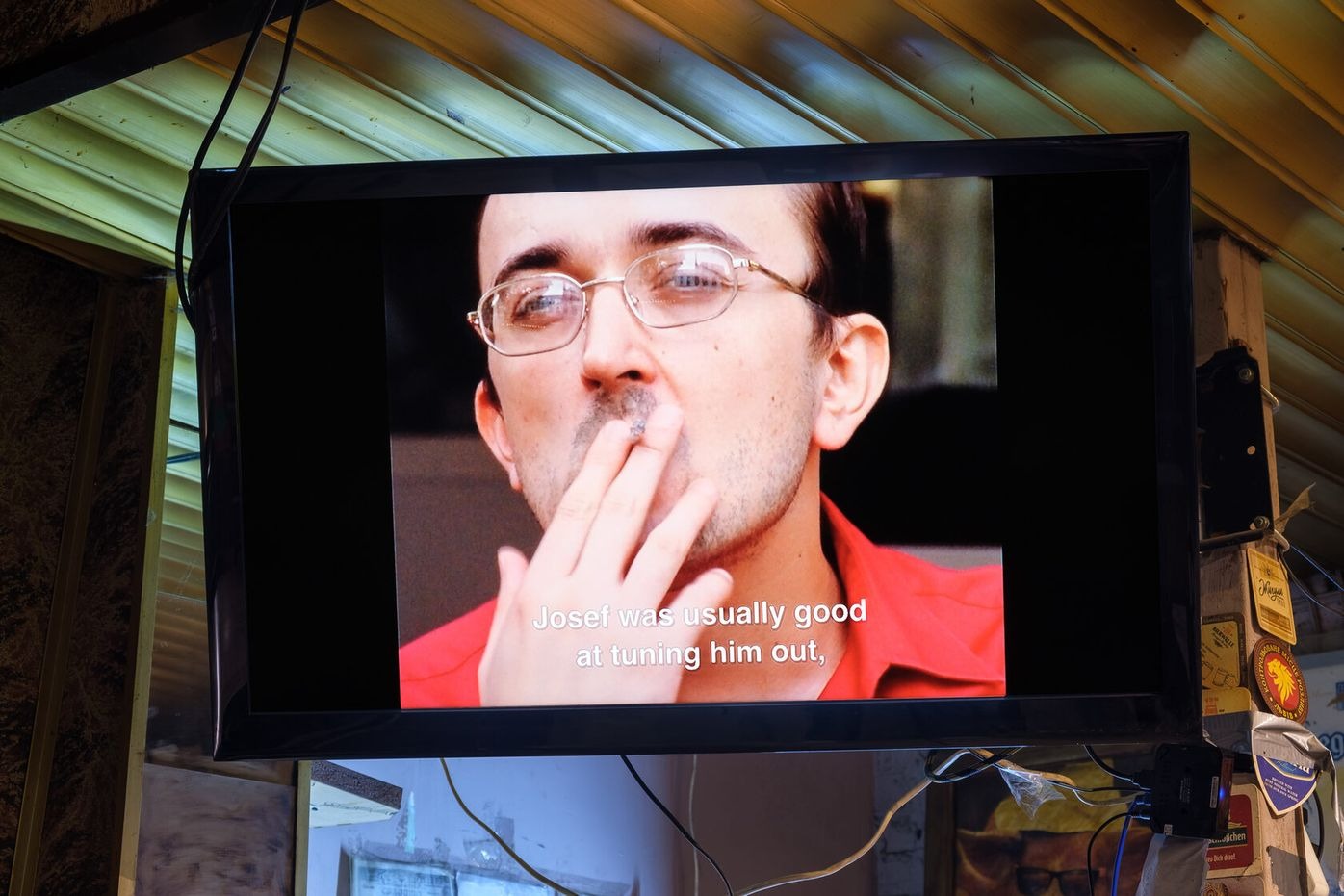

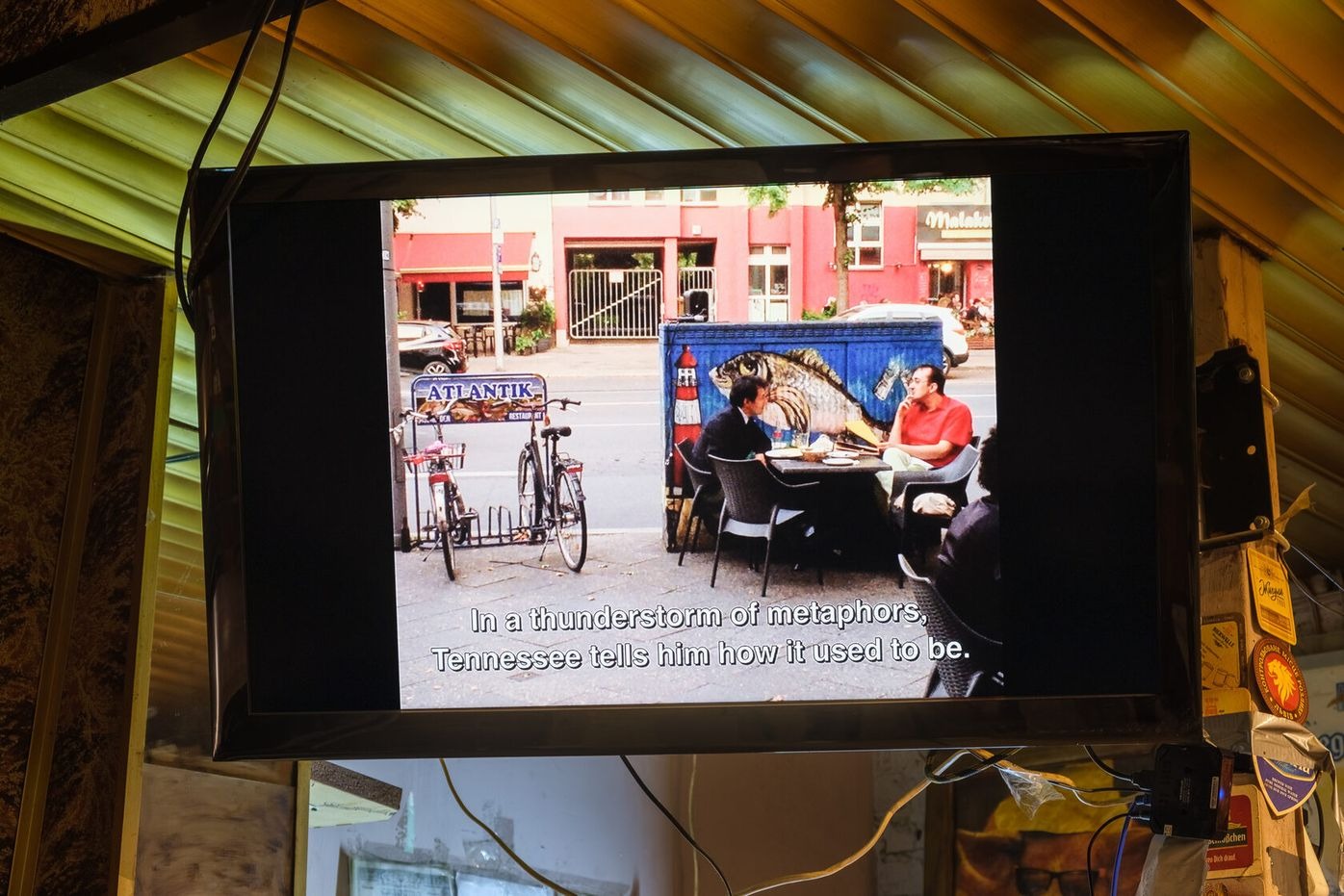

In their artistic practice, Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff rely on their own experience of founding and running venues to investigate the nature of shared spaces: their inner structures, politics, and economics. Collaboration is central to their process — they involve a wide range of participants in creating their works, and explore the relations within these close-knit or newly formed communities. Using a variety of mediums, such as theatre, text, and photography, they reconsider the common scenarios from the life of these spaces and turn them into amusing and occasionally paradoxical spectacles.

For the Future Generation Art Prize 2021, Henkel and Pitegoff present their ongoing project Paradise, a TV series shot at their own bar, TV, in Berlin, cast with regulars, employees, and neighbours. The plot unfolds in the fictional bar Paradise in 2023, where the bartenders are forced to work as newscasters, following their absent boss’s desire to transform the place into a hyper-local news channel by reading prepared speeches to the bar’s customers via teleprompter. Over the course of the show, the employees attempt to take control over the bar’s narrative.

For the project, the artists collaborated with four Kyiv-based bars and clubs, which host monitors playing two episodes of Paradise on loop for the duration of the exhibition. As an act of sharing, pieces of furniture from these spaces have been swapped with furniture from TV, and are presented in PinchukArtCentre as seating for the screening of a trailer for Paradise.

Paradise, 2020 – ongoing.

Exhibition at Closer

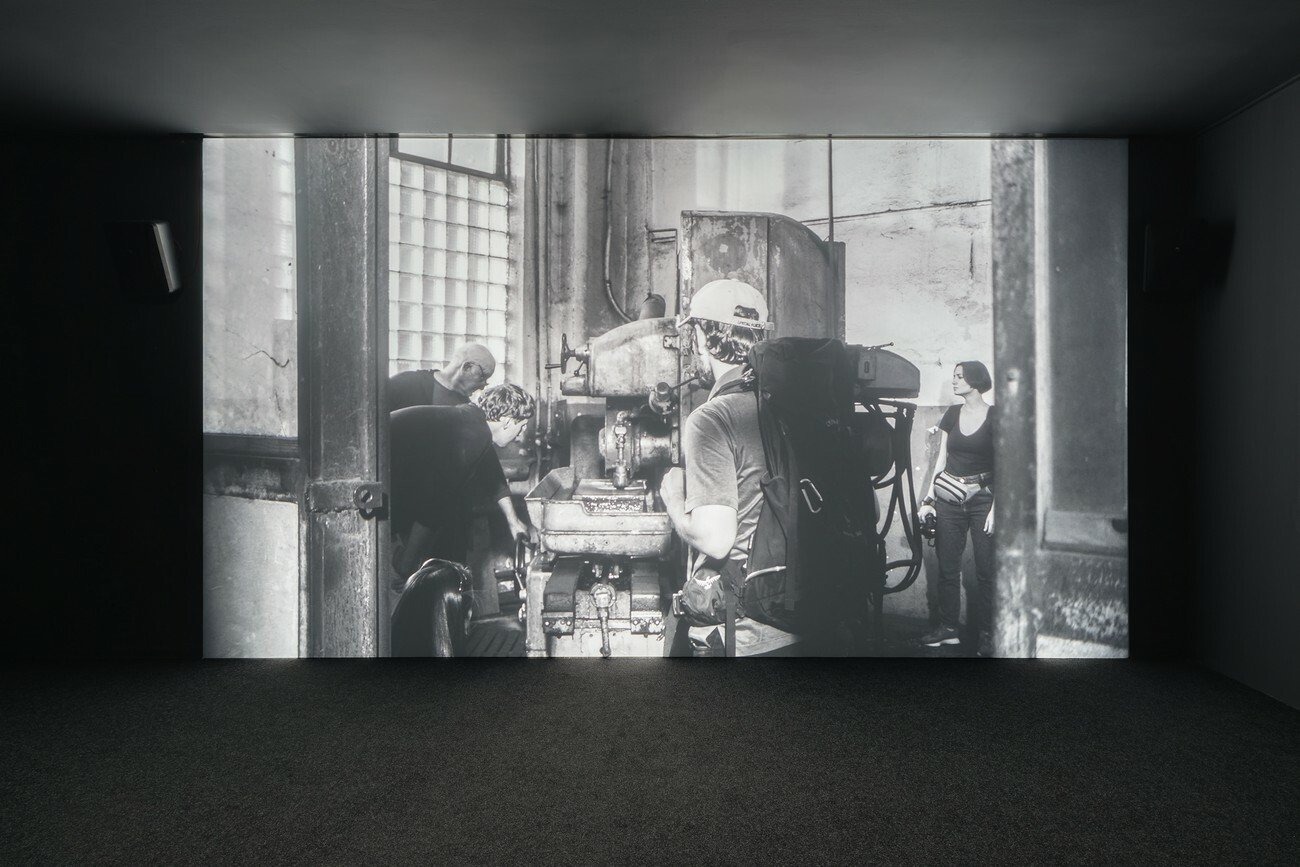

Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei have created a new video work for the exhibition. The filming takes place at the semi-operational Promprylad factory in Ivano-Frankivsk, part of which has been given a new lease of life as a creative cluster. The process of active reconstruction in which the plant for manufacturing industrial instrumentation has found itself since 2017, is gradually revealing the differences between the emerging and coexisting spaces on its premises. Reflecting on these changes, one can see the three modes in which the plant operates: technological production, creative entrepreneurship, and the transitional state of dismantling, carried out by a team of construction workers.

How It`s Made shows the audience the factory as an independent entity along with the people who work there, both native engineers and new tenants: employees of IT companies, architectural agencies, craft workshops, and educational projects. Malashchuk and Khimei register the current state of transformation and the arrival of “new era” employees, who are gradually occupying more and more space. Far from the rapid transitions of the industrial revolution from manual to large-scale machine production, the dynamics of Promprylad encapsulate the tensions of a post-industrial world.

Acknowledging this, the artists give the plant’s senior workers a symbolic farewell, prompting direct interaction and inviting everyone involved to join the event. Employees of the creative cluster, who represent the alternative production that has taken over the formerly industrial site, design a “new uniform” for technical staff. Dressed in modern clothes, former engineers leave the place where they have worked for many years and gradually blend into the city.

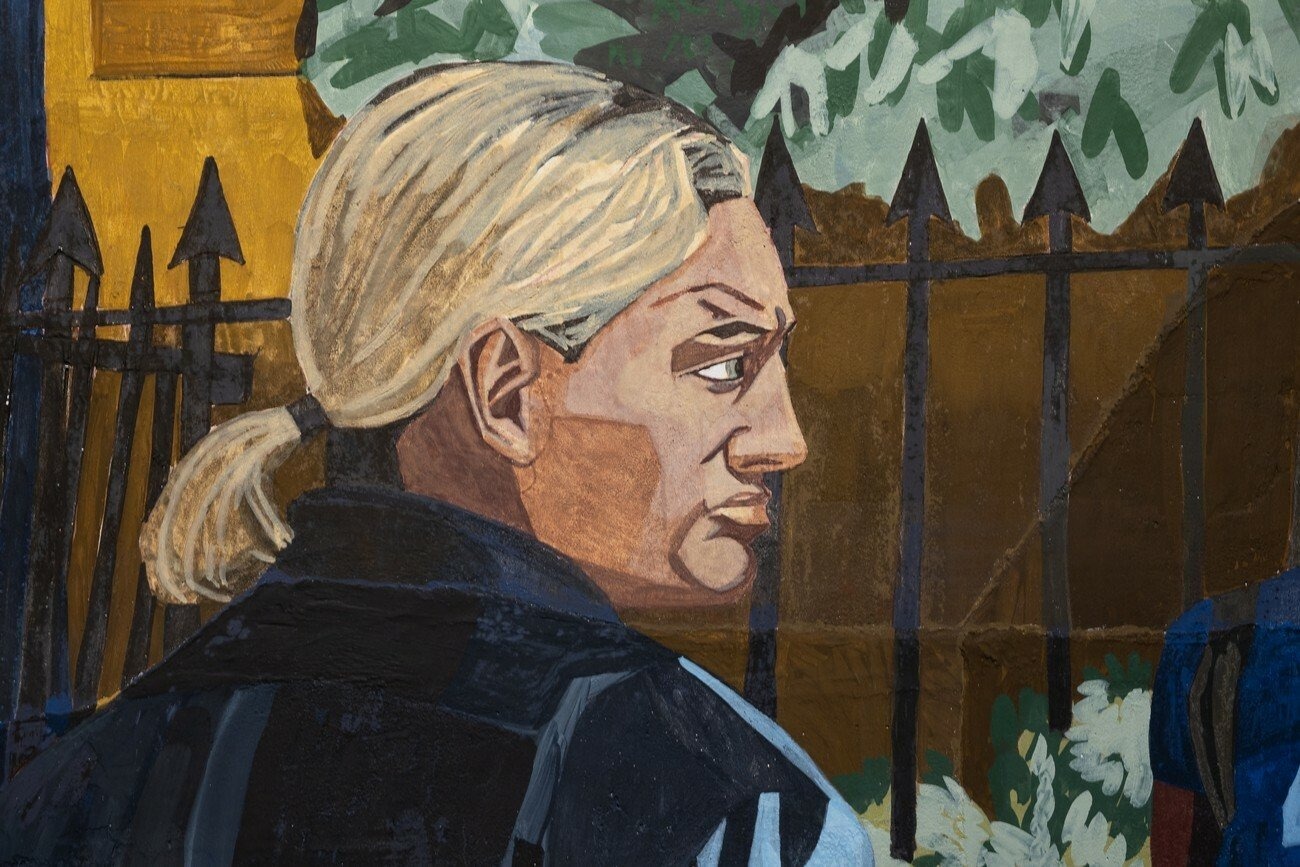

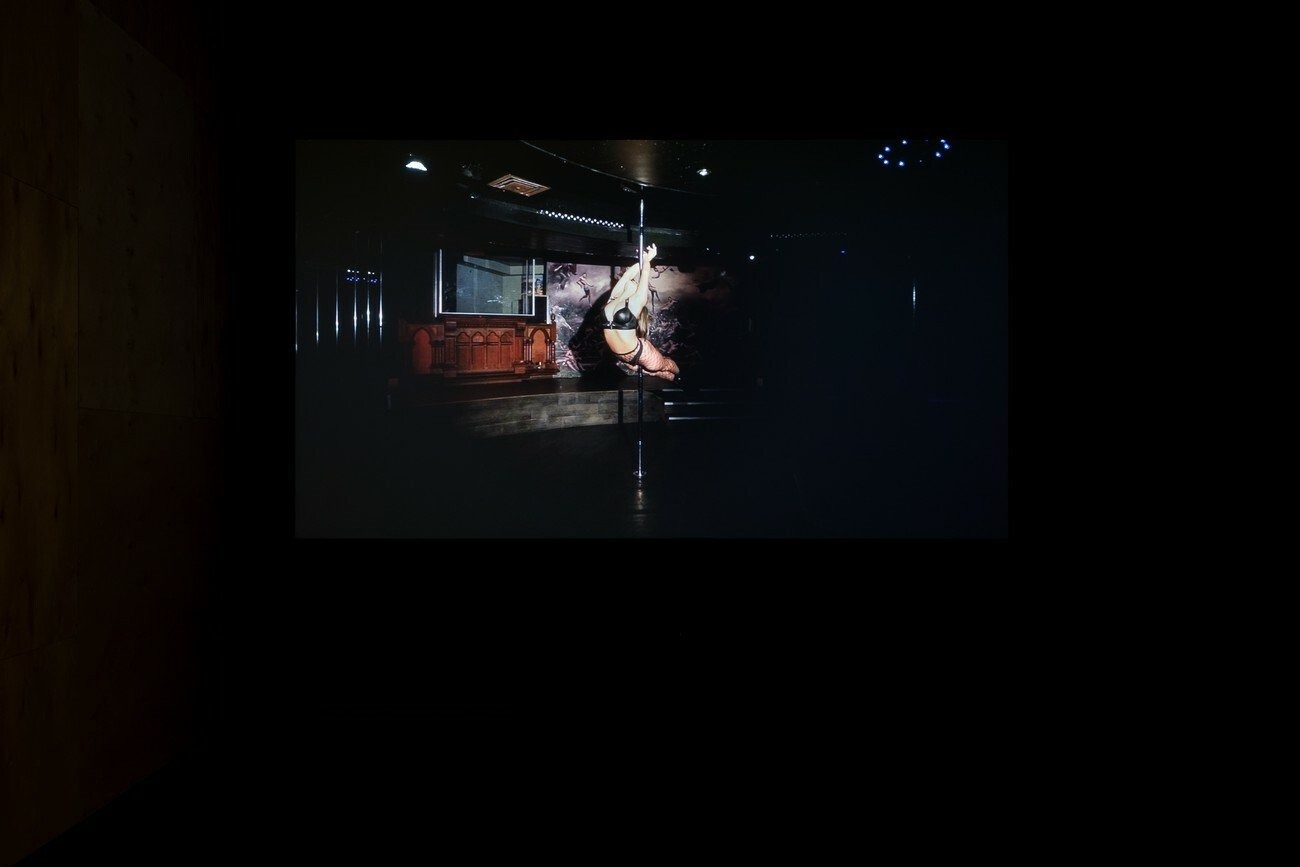

Hannah Quinlan’s and Rosie Hasting’s works for the Future Generation Art Prize 2021 investigate the history, politics, and aesthetics of LGBTQ+ culture. Working across film, drawing, installation, performance and fresco, Quinlan and Hastings address the sociocultural and political structures that reinforce conservatism and discriminatory practices within and around the LGBTQ+ community.

The film In My Room is a successive continuation of UK Gay Bar Directory, a moving image archive of gay bars that responds to the systematic closure of LGBTQ+ dedicated social spaces. Shot in Bar Jester and the Core Club in Birmingham’s gay village and Shoeburyness Fort in Southend-on-Sea, In My Room explores how a culture of male sex in public and mens-only gay bars links to a broader culture of (white) male dominance socially, historically and culturally. Highlighting the impact of gentrification upon the city and its communities, the film explores the relationship between masculinity and capitalism, and suggests a subconscious reproduction of power in public space through behaviours, codes and gestures.

Public Affairs references hate crime legislation and reveals the inequalities between privileged and discriminated groups within the queer community. In this fresco series, the artists reconsider the role fresco has played in society and culture and the balance it strikes between ideology and symbolism. Given that fresco painting is often found in places of political, legal and educational importance, the artists have set these works in central London locations, such as Green Park, a zone of elite power but also the location of Gay Pride parades and a historic cruising ground for gay men. In these works, the artists depict images that represent this unruly clash of registers, such as the disciplining power of the state and the rebellious energy of the people who gather in these spaces.

Vernissage

The Award Ceremony