Imaginary Distance

A solo exhibition by Lesia Khomenko

The exhibition Imaginary Distance unfolds as both a journey through the recent history of Ukraine and an exploration of Lesia Khomenko’s own artistic development. Bringing together more than fifty works, it traces her trajectory from her early paintings in 2005 to the most recent works created today. Across twenty-five years of practice, Khomenko has persistently challenged herself to discover new ways of addressing both form and subject, constructing an artistic language that critically rethinks visual soviet heritage and turns to the traditions of Ukrainian painting and deliberately resists to be confined by it.

Throughout the exhibition, Khomenko’s signature style remains unmistakable — broad, decisive brushstrokes and a distinctive palette that together grant each work a singular presence. While she challenges the limits of medium of painting itself, her vocabulary transforms together with her subject matter that is inseparable from her environment: a profound engagement with Ukraine, its people, and its most recent history. In her canvases, one encounters a critical reflection on society, personal stories as well as an articulation of collective experience.

Lesia Khomenko, “Imaginary Distance”, 2025. PinchukArtCentre. © Photo: Ela Bialkowska,OKNO Studio

Throughout the exhibition, rooms function as liminal spaces, suspended between distinct historical moments, where different moments in time are brought into dialogue. This curatorial strategy consciously produces a field of tension, compelling the visitor to wander across temporal thresholds in Ukraine’s history.

The opening of the exhibition stages such a collision between two temporalities: the protests of pre-Maidan Ukraine (series Mixed Feelings -2013) and the current full-scale war (Injured Russian Soldier – 2024). In this juxtaposition, society is shown as both divided and united, fragile and resilient. It is precisely in the interval between these works that a conceptual gap emerges — a liminal space that invites reflection on the writing of history, its artistic reflection and the imagining of possible futures. Such oscillations between temporal registers are consistent throughout the exhibition, resisting linear narration and foregrounding the multiplicity of historical experience.

Lesia Khomenko, “Imaginary Distance”, 2025. PinchukArtCentre. © Photo: Ela Bialkowska,OKNO Studio

Parallel to this temporal play, the image of the human body is a central subject, being continually reframed and re-invented, moving from an academic depiction of the body to an interpretation of the body as social and political, which ultimately becomes defined through the dehumanizing gaze of war technology.

Lesia Khomenko, “Imaginary Distance”, 2025. PinchukArtCentre. © Photo: Ela Bialkowska,OKNO Studio

Khomenko depicts the body, critically mimicking and referencing Soviet realism in series of works such as Wonderland(2010) and Giants(2007) while also creating works that are fundamentally anti-monumental gestures such as Friends(2005) and Drawing on Maidan series(2013-2014). From there, Khomenko moves towards the dis-integration of the human body itself. Covert Surveillance shows the human figure as a target, depicting what is under the skin in search of vulnerabilities. In the same room Radical Approximation transforms into abstraction, aligning with snipers perspective or firearm optics. This comes to a culmination in the series Perspektyvna (2018) and Unidentified Figures (2022–ongoing), that together create a room filling installation, interrogating the visibility of the human body under conditions of war. In Perspektyvna series(2018), soldiers are half-concealed behind branches, echoing the artist’s own vantage point from her studio. While in Unidentified Figures (2022–ongoing), depict military images blurred for reasons of security are transposed into painterly form. At this point we moved from the human figure as an undividable sculpture, ironically referencing a historical heroism, to the body that is hidden and abstracted. Finally it becomes divisible and targetable, then reduced to a single dot,seen by military technologies in the work I’m a Bullet (2024).

The exhibition unfolds as a journey through time and space but also as a sustained exploration of Lesia Khomenko’s obsession to expand painting beyond the two-dimensions of the canvas. This third trajectory finds its most powerful articulation in Battle in the Trench, where painting is transformed into an immersive environment. Here, the subject of representation shifts decisively from the painted figure to the visitor, who becomes an unwitting performer. By walking through a constructed “trench,” whose claustrophobic architecture is modeled on footage from drones and soldiers’ body cameras, the viewer is physically implicated in the logic of war. At the same time, those observing from the gallery’s upper floor occupy a drone-like vantage point, gazing down upon the moving bodies below. The visitor becomes the painted subject, folded into a choreography of surveillance and exposure.

Lesia Khomenko, “Imaginary Distance”, 2025. PinchukArtCentre. © Photo: Ela Bialkowska,OKNO Studio

Khomenko is driven by her inner urgency of challenging the medium of painting itself as well as the urgency of her subject matter, the lived realities of war, protest and friendship throughout the last 25 years in Ukraine. What began as an engagement with Ukraine’s collective history culminates in a rethinking of what painting can be. Khomenko is not confined by surface or mere representation. Her work transcends the given canvas, becoming a performance of lived experiences. Her work is both testimony and experiment, it is painting as well as sculpture. It speaks to the fragility of the human body while empowering a collective agency through her critical reflection of Ukraine as a space, a country and a society.

Curator: Björn Geldhof

Assistant curator: Oksana Chornobrova

Manager: Ilona Demchenko

Technical management: Evhenii Hladich, Valentyn Shkorkin

Artist’s assistant: Kseniia Samopalova

The first room combines a war-deformed portrait of a person and a portrait of Ukrainian society from before the revolution and hostilities began. Scattered figures in the crowds in the images seem to foreshadow the turmoil of war and the depersonalisation of human beings. In the works represented here, the human body becomes an object, almost dissolved in some way — first as a part of a picture, and then as a military target.

In Injured Russian Soldier, the artist reflects how an image created by military means penetrates modern visual culture (from social and conventional media to art). The painting shows a wounded Russian soldier from the viewpoint of a drone. The human perspective changes to that of the machine, and the human body is perceived as a target or an object designed for a specific function.

The Mixed Feelings series can be viewed today as a portrait of a mutilated society with blank spaces to represent its losses. However, works created as far back as 2013 seem to illustrate how the public felt on the eve of fundamental change. The crowd and the body fall into pieces and reassemble into new entities. Thus, the works embody one of the key themes in Khomenko’s artistic practice, which the viewer encounters throughout the exhibition. The artist deconstructs and disassembles the human body and uses its components to create the composition. The body is used in the same way as the other elements of the image, like the gaps that fill the canvas.

In the work from the Wonderland series (2010), the acrobats form a holistic architectural form against the backdrop of the Carpathian landscape. This artwork embodies the conflict between the outdated collectivist ideology and aggressive privatization of the aughts, which encroached on the natural landscape of the Carpathian Mountains. At the same time, the beauty of the Ukrainian landscape shown here is threatened by the coming war. This is pointed out by a folded painting from the MPATS series, which symbolically transforms into a weapon.

By depicting acrobats whose bodies are assembled into a single composition, Khomenko refers to the Soviet past, where athletic exercises and competitions were part of ideological education. The landscape of the Carpathians, where the athletes are placed, embodies harmony, but at the same time is a centre of chaotic privatization and construction. Thus, Wonderland outlines the political and ideological uncertainty that Ukraine faced for a long time: torn between its decaying Soviet heritage and chaotic capitalist rule.

In the MPATS series, paintings rolled into tubes are reminiscent of portable anti-aircraft missile systems. This is how Khomenko transported paintings at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. Later, painting helped the artist tell about Ukraine and present it in cultural confrontation with Russia. This work reflects society’s new relationship with the war, where weapons have become an everyday part of civilian life.

How do we perceive a human? The works presented herein offer different perspectives: human as a social unit, as an anatomical body, as a historical and political subject — or as a military target. Moving from the ‘new hero of everyday life’ to a Maidan participant, the human figure is soon viewed primarily as a physical body — eventually becoming blurred in the gunsight, the optics of which are reproduced by Khomenko.

In the Giants series, the artist uses techniques typical of the socialist realist style to depict an ordinary person. This work presents a worm’s-eye view of a recognizable social archetype from the 1990s and early 2000s, visually enlarging the Soviet hero. Thus, the central figure in Khomenko’s art is an everyday figure devoid of ideological pathos.

The works from the Drawing on Maidan series depict the Revolution of Dignity participants. After joining the Maidan protests, the artist gave the protesters the original portraits and kept the carbon copies for herself. Quick sketches were a way to reflect and document the faces of people who were part of historical events. The artist’s personal involvement avoids mythologizing the events, instead showing a faithful representation of how everyday people manifest their own political agency.

In Covert Surveillance, a person is primarily viewed as a body. Depicting the anatomy of a body through the impersonal figure of a soldier, Khomenko draws a parallel between the view of an artist and a sniper. A person is perceived as a set of body parts that can be injured or rendered as art. As the war unfolds, the object-first view becomes increasingly dominant. Finally, in Radical Approximation, the person disappears, turning into a spot at the centre of the target. Divided into four sections, the canvas reproduces the optics of a firearm sight. In this way, Khomenko shows how technology and weapons determine the view of reality.

People with ordinary civilian pasts join the army to fight for the future. Carefree portraits of the artist’s friends are juxtaposed with an image of her ex-husband, previously a musician and an artist, who joined the military following the full-scale invasion. The central work of the room, depicting an attack on a civilian hospital, shows how civilian life is destroyed in all its dimensions; how peaceful life changes into the need to defend oneself.

In the works of the Superstars series, Lesia Khomenko captures her friends’ moments of joy and fun. One of the first series in the artist’s practice explores how photography changes the portrait genre. The paintings resemble reportage photos: the artist’s friends are spontaneously captured mid-movement or comically pose for the pictures. Contrasted with the other works in the room, Superstars serves as a nostalgic reflection of a carefree youth and past which quickly vanished when war broke out.

Max in the Army is based on a photograph of the artist’s then-husband taken at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. The combination of the figure’s ordinary clothing and saluting gesture suggests he joined the army, and demonstrates the blurring of the lines between civilian and military roles.

The work Explosion in the Hospital from the Montage series embodies a new type of historical painting. Reflecting on the visual image of war produced by technology and media, the artist collages frames from a 10-second video recording the shelling of a civilian hospital. The painting captures the instantaneous destruction of a civilian object by a missile and simultaneously reflects the rapid exchange of documentation in the digital space.

The faces of the military are often anonymous, their actions invisible or unnoticed, and yet our everyday lives depend on their actions. This room emphasizes the ubiquitous presence of the military in our reality. At the same time, there is a change in the way a soldier is viewed: from a distant viewpoint in the Perspektyvna series to the close-up of the blurry Unidentified Figures and visualizations of the past in the Stepan Repin series.

Khomenko has consistently represented soldiers in her work since 2009. In the Perspektyvna series (2021), military figures are hidden behind branches and depicted at a specific angle. The artist portrays soldiers whom she saw every day from the windows of her workshop, located next to a military unit. The painting reflects the artist’s own perspective — but also that of society, as if spying on the soldier.

The paintings from the Unidentified Figures series (2022–ongoing) reproduce pictures taken by military servants. They usually pixelate and blur images to hide any identifying information from the enemy. The paintings reflect how the image of the soldier becomes abstract and the real person behind it becomes uncertain. The final work in the room, A Moment of Shot (2023), reproduces a frame from the video capturing the moment a shot is fired. The static and figurative image dissipates and the image of the soldier and wartime reality shatters into pieces that become increasingly difficult to put together.

In the Stepan Repin series (2009–2011), the artist turns to her grandfather’s journals where he shares his experiences of World War II. Drawing on history and her relative’s memories, Khomenko challenges the Soviet narrative around these events. In contrast to the heroic image of the soldier in socialist realist painting, this work presents an ambiguous depiction of a warrior at a moment of fear and vulnerability.

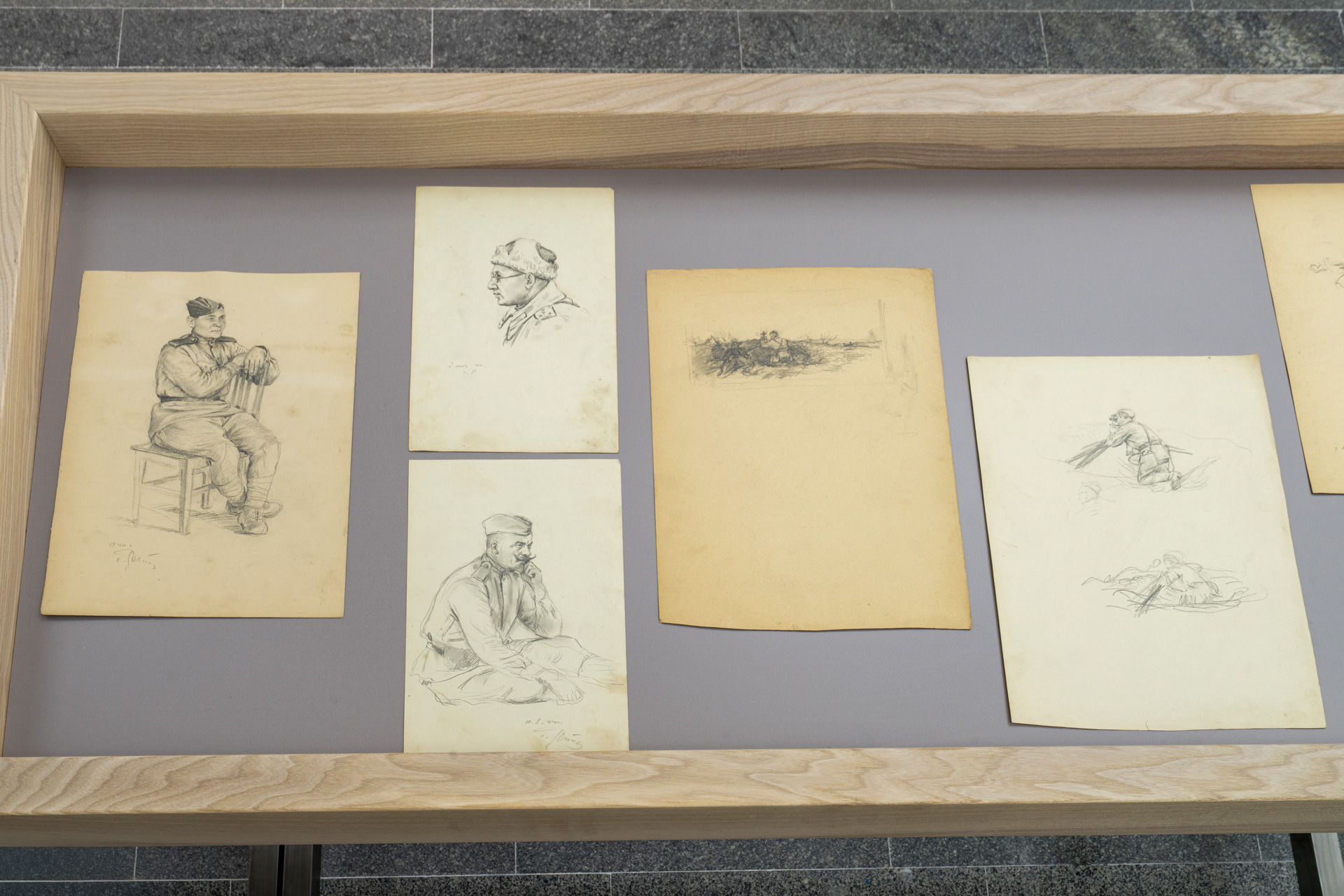

Despite seemingly ubiquitous photo and video documentation, the clear vision and understanding of the war increasingly disintegrates, turning into abstractions. The concrete, corporeal image of a woman seems frozen in time, in contrast to the fleeting moments of the war. This figure is either lost or is the only one to maintain connection with physical reality in a sea of digital media. Sketches by Khomenko’s grandfather, a World War II veteran, serve as fragile material evidence that has become inferior to modern digital records.

I’m a Bullet reproduces a frame from the camera of a kamikaze drone hitting its target. Turning to modern tech, Khomenko shows how it has become the dominant means to perceive reality. The illusion of comprehensive documentation disappears as the camera explodes, leaving only spots and pixels.

The work A Moment of Shot reproduces a still frame from a video capturing the moment of the shot. The abstract image still retains a connection to reality, yet it becomes increasingly difficult to discern. The diptych A Moment of Explosion in the Trench from the Montage series contains a snapshot from a video where the drone operator remains focused despite an explosion next to the trench. However, the diptych does not show this. On the contrary, the soldier, while still recognizable in the first image, becomes a collection of coloured bands and spots in the second. With its intertwining of the digital and physical realms, here the artist creates a new type of abstract artwork which reflects our modern reality.

In this work from the Giants series, Khomenko uses the language of Socialist realism art to depict an ordinary woman. Her figure moves from the Soviet past to the present of an independent Ukraine, eventually facing the war. The literal image of a person gives way to blurred technological images. The woman stands firm, despite being faced with horror.

In the new work Battle in the Trench, Lesia Khomenko symbolically reproduces the architecture of a series of trenches based on footage from real battles. As they walk through the narrow passages, the viewer unintentionally becomes part of the performance — or an object to be observed by those looking at the work from above. Visitors on the next floor look down at the ‘trench’ and people in it from something akin to the viewpoint of a drone as it flies overhead and identifies targets. The war symbolically becomes a stage where all eyes are directed. Through numerous photos and videos, modern media creates an illusion of closeness or even involvement, while conversely distancing viewers from reality.

Continuing her exploration of the pictorial medium, the artist worked with a restorer to transform the canvases into an immersive structure. The design of the ‘trenches’ is based on videos from drones and soldiers’ body cameras. This form of documentation shapes our modern image of war, and is reflected in the work as it offers a comparison of two perspectives: a body camera, as close as possible to the person participating in the events, and the mechanistic, all-encompassing vision of a drone.

In this hall, the World War II context features for the second time during the exhibition. Like the works from the Stepan Repin series, Khomenko rejects the Soviet ideological narratives about this war. Here, the artist refuses to depict it figuratively, as in the socialist realist prototype of her work, and leaves only colour and movement. Thus, an abstract canvas becomes a way to depict events that have not been experienced. Similarly, Khomenko depicts modern warfare using blurred and fragmented evidence from cameras and drones.

Fedir Usypenko’s The Response of the Mortar Guardsmen, to which the artist refers, is a typical example of the mythologized depiction of World War II in official Soviet art. By stripping the work of any specificity, Khomenko eliminates the ideological interpretation of the events of the war and the socialist realist language that illustrates it. Lines and spots alone cannot communicate the Soviet version of World War II.

At the same time, the sketches by Stepan Repin, a World War II veteran and the artist’s grandfather, directly reflect the experience of a participant in the events. These hastily made drawings served as a way to record what he personally saw and lived through. In contrast, epic socialist realist paintings were created several years after the war, since their imagery was carefully constructed in line with ideological demands. Thus, diary sketches are evidence of historical events, providing a connection to the past that is not mediated by Soviet ideology.

The war turned the Black Sea and Crimea into a combat zone, transforming its former and current residents into objects and subjects of political and armed conflict. Deformed characters watching the sea battle at this former holiday destination show the irony in how everyday life and leisure intersect with the context of a conflict.

Sea Battle is based on a video recorded by a Russian sailor during a Ukrainian drone attack on an enemy warship. Here, Khomenko creates a new type of contemporary battle painting that embodies a digital vision of war. By combining frames from the beginning and end of the video, the artist recreates the dynamics of both the confrontation itself and the video recording. The semi-abstract image of the light of explosions and gunfire, the darkness of the night and shipwrecks, captures the fear of the soldier behind the camera.

In the works from the Several Stories and Objects series (2020), Khomenko spies on random Ukrainians and acquaintances on holiday in Turkey, listening to their conversations and disagreements with Russians around the occupation of Crimea. The artist paints portraits based on covertly photographs and stretches the canvases on deck chairs. The work embodies the deformation of the image and the story alongside the usual course of life and leisure of people who lived or spent their holidays in Crimea. A carefree pastime became impossible, with the war sparking disputes on occupation, the search for identity, the experience of leaving home, and the need to narrate it.

The work from the Nomadic Self-Portraits series reflects the experience of displacement and a change in identity caused by the full-scale invasion. Khomenko’s life and artistic practice have since become mobile — like a painting rolled up in a tube that the artist carries on her shoulder.

The artist uses elastic fabric as a canvas, and by stretching it onto a stretcher, she deforms the image. Thus, the distorted self-portrait embodies an identity that changes with relocation and constant movement. Simultaneously, Khomenko treats her own image with irony. Continuing her work with fabric, she shows how the medium of painting transforms the human figure. Thus, her figure underwent change yet became flexible due to the constant need to adapt.