Tuesday through Sunday from 12:00 until 21:00

Closed Monday

Admission is Free

Alevtina Kakhidze in conversation with Tatiana Kochuninska

Tatiana Kochubinska: The PAC-UA Re-Consideration project is an attempt at establishing connections between different generations of Ukrainian artists. What does this mean to you? Has this project become an occasion for analyzing your own artistic practice?

Alevtina Kakhidze: Honestly, yes. I had almost been persuaded by Oksana Zabuzhko’s thought, expressed in her book Notre Dame d’Ukraine, that Ukrainians are unable to build connections between generations and experiences, that they always build everything anew, again and again. This is why we get so many stories of severed connections and possibilities. Yet when I was invited to create an exhibition whose main idea was “reconsideration”, I decided not to refuse the offer and to think it over. This is how I found out about artist and their work. Ukrainian ones. I started reflecting on the way that others had influenced my thinking, and this was the starting point and beginning of my own work.

TK: Did you find answers quickly? How did Vasily Tsagolov emerge as a central figure?

AK: Actually, very quickly. When there is a real influence, you don’t have to think for long. The first answer to the question what had an impact on me, what shaped me, was science fiction. That’s precisely what made me into an artist. Science fiction was the only thing that gave me moments of freedom in childhood. Reading was more dependable than looking at black and white reproductions of paintings. Then, speaking about more recent past, I recalled Tsagolov’s work Solid Television Studio from 1998, which I saw at the exhibition Come-In at the Centre for Contemporary Art at NaUKMA in Kyiv 2002.

TK: So that was in 2002, when you studied at the National Academy of Fine Art and Architecture. Were you already conscious of your own artistic individuality? How did Tsagolov’s construction of realities correlate with the development of your performative practice and story writing?

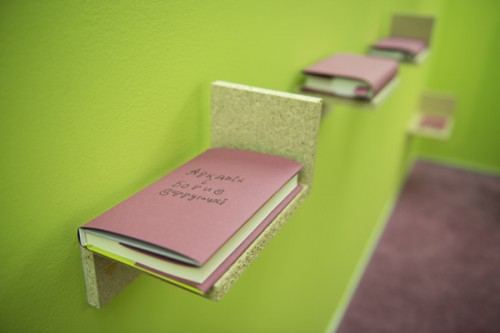

AK: Back then, I had no experience writing stories, had made no attempts even. I did my first performance in 2006. What struck me about Tsagolov’s Solid Television Studio was the same quality: the viewer of his work ended up in a world constructed by the artist and found an answer there. This is a complete installation. In international art, one of the most famous artists creating total installations is Ilya Kabakov. He was born in Dnepropetrovsk, actually. In Ukrainian art, however, there have been virtually no artists working with total installations. For me, an installation means creating a space in which everything it contains has been chosen by the artist. Nothing around the viewer is random, the viewer, in fact, has to become a part of this space. This is actually how television works – television, too, is a sort of construction of reality.

ТК: So how does the construction of a reality in your new work, TV Studios / Rooms without Doors, relate to science fiction?

AK: In an installation, the artist creates their own world, demonstrating a particular view of reality. Science fiction writers also construct their own worlds. When I speak of science fiction, I am aware these are stories written by real people and that nothing supernatural happened to them – they never visited fantastic planets. Everything they have written is a result of an astonishing faculty that humans possess: imagination, or fancy. When a person is imagining something, memory is the only material at their disposal. It’s impossible to construct a new imaginary world or situation without some images drawn from memory. Nevertheless, it’s quite another question how one remembers reality, how long one can retain it in memory so as to combine different elements and build new connections later. We presume that we can combine reality and unreality, which, in its turn, can assist us in building a new reality – in fact, this is what art does. Art is an invented form, an invented story. When you enter the space of art, every object, sign and symbol has been transformed by the artist, imagined differently by them.

ТК: You work presents a world produced by the artist, a world in which reality and fiction, memory and imagination transform into one another. Reality is staged, imagined or simply seen through the window.

AK: Yes, that’s exactly right. The starting point for me was the reconstruction of Tsagolov’s installation. To my mind, his work illustrates how you are able to show a non-existent reality as actual reality in a TV studio. Yet because viewers can see how this is done, they are not deceived, they receive knowledge instead. The most significant detail of the installation is a photograph. The photograph, shown from a TV screen, puzzles the viewer: is it a snapshot of the real world (as seen from the window of the 4th-floor space of PAC) or a picture created in a TV studio? The back of a chair shown in the photo is the only element indicating that this reality is commensurable with the reality of the viewer. So there are three landscapes standing for three realities in the installation: one landscape is a picture made by a photographer and edited in Photoshop, another is produced by a visual artist, yet another can be simply seen through the window. Roughly speaking, there are three ways of consuming reality. And more, if you go back to my childhood, science fiction, my first impressions…

ТК: What are the symbols from science fiction that became transformed in the project?

AK: The installation with the purple carpet is itself a direct reference to Clifford D. Simak’s work All Flesh Is Grass, where the hero finds himself in a parallel world. The only thing that exists there is purpleness, purple grass. There is nothing else there.

ТК: The title, Rooms without Doors: is it about realities overflowing into each other?

AK: Yes, absolutely. With TV studios, it’s not about walking around and watching, rather it’s about what flies out of these places – but not through the door.

ТК: Still, there is one little door there.

AK: A real door, an unreal door, an imaginary door, a painted door which can seem real.

ТК: During the exhibition you will make performances based on the stories you have written. Tell us about these stories.

AK: One can say I am a science fiction writer. I blend real and imagined things. This is probably my method. My stories can throw a person off balance. I like my viewers to be in this state – they have to wake up! If I invent a hyper-untruth and put it next to a truth nobody believes in, then as a result the truth that looked like an untruth seems more credible.

ТК: This is similar to montage. When the juxtaposition of different frames makes us interpret things in a different way.

AK: Yes, I have been using this method since I was a child, inventing something that can baffle people.

ТК: A recipient of your stories has to actually choose between truth and untruth, as if between two evils. Adding an absurd element to a truthful story, you manipulate the viewer’s perception. Why is manipulation so important to you?

AK: I would say that this is provocation, not manipulation. Manipulation is using someone’s weaknesses. For an artist, it’s more suitable to use provocation – in order to find society’s pain threshold and engage with it. To my mind, provocation in art is similar to the Mantoux test – it’s aimed at establishing a diagnosis. If the artist’s provocation triggers no reaction, the pain threshold hasn’t been reached. So while there is a scenario of possible reactions, viewers can never be completely sure what will happen next. For instance in my stories, which I read during the exhibition: when I am reading the performance text about representatives of flowers and dogs participating in an election, in effect I am talking about human egocentricity. We have long since changed the fate of such creatures as dogs, for example. They cannot go back to the world they once left. They don’t have a territory of their own. I see this news story as a provocation: if people do not even admit the idea of dogs being representatives in power, it reflects on their egocentricity.

ТК: At first glance, these stories appear absurd, but on reflection they seem to uncover and highlight absurd elements of our reality.

AK: Each news story has a political aspect. In the first place, these stories activate the mind – you start drawing your own conclusions. One critical thought is disputed by another critical thought – a corridor of thoughts for practising the mind. At the same time, my stories are funny. Humour is always at a distance from reality. For instance, the story in which I suggest that MPs undertake an internship in the garden. This is funny, but then we go deeper into the matter: one plant is super strong and is not afraid of drought, while another grows slowly and needs watering, and the one that is quick prevents the growth of that which is slow. For me, this is the problem of minorities, of small states next to aggressive superstates. For me these things are at once simple and complicated.