Research platform: Anonymous Society

“Anonymous Society” features works by Sergei Anufriev, Yevgenia Belorusets, Sergey Bratkov, Oleksandr Chekmenev, Oksana Chepelyk, Zhanna Kadyrova, Victor Palmov, Evgeny Pavlov, Serhiy Popov, Kirill Protsenko, Roman Pyatkovka, Larisa Rezun-Zvezdochetova, Oleksandr Roitburd, Vasyl Tsagolov, Leonid Voitsekhov.

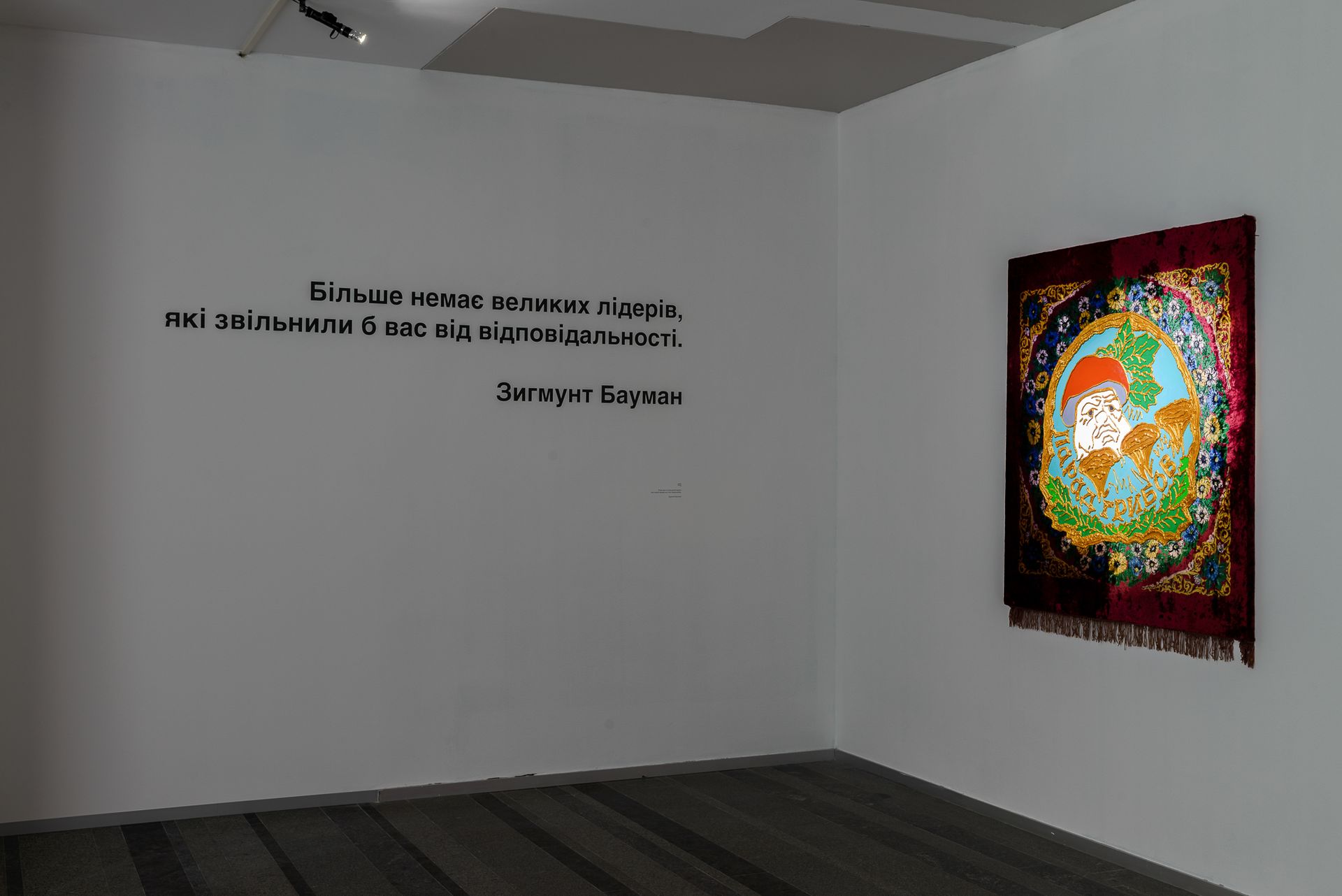

The exhibition explores the period of anomie that Ukrainian society was plunged into after the collapse of the Soviet Union (1991), and that it languishes in to this day. The term “anomie,” coined by the French sociologist Émile Durkheim, describes a crisis-ridden transition period societies land in after political turmoil and changes in values when “the old gods are aging or are already dead, and others are not yet born.”

These situations when new behavioural paradigms are not yet formed raise the question of the role of individuals, their destructive potential and desire to make their voices heard, or to remain voiceless.

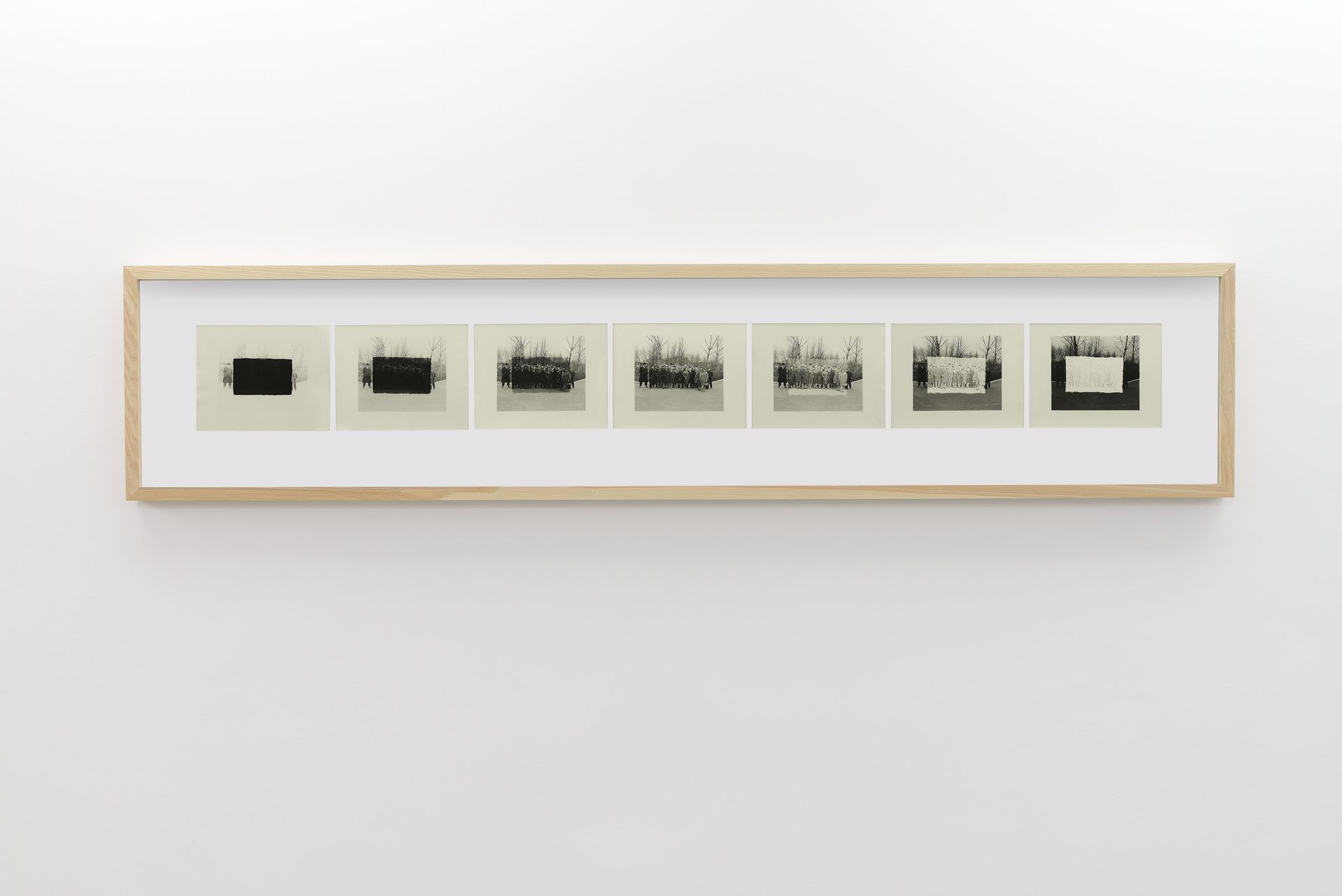

The performance of the Odessa-based artist Leonid Voitsekhov, entitled “They’ll Settle the Score With Us for It” (1984), marked the starting point of the exhibition. The performers carried a poster with this slogan through Odessa streets as a reaction to a disaster that left the city without power and water supply. When the police detained the performers and asked who the “they” of the poster might be, the artists replied, “The elemental forces.” Within the context of the exhibition, this gesture denotes the metaphorical division of society into two opposite forces: us and them.

The exhibition consists of several chapters. The first addresses individual existence within the ideological standoff, from the emergence of heroes to their gradual devaluation; existence among double standards; and individuals evolving against the backdrop of changing political scenery. Chapter 2 treats self-awareness, inner struggle, collective memories and experiences. The last chapter deals with intimate physical experiences; addressing them is a manifestation of resistance against control over private lives.

In essence, within the context of the exhibition, “anonymous society” is a metaphor for the absence of society as such. Individuals had inherited distrust for discredited authorities, yet, driven by inertia, continue to live under the unseen gaze of the Big Brother. The exhibition seeks to discover the “I” and make it manifest. It foregrounds individuality, making its voice heard in the anonymous field of the deformed social and political reality, within the sphere of personal memories and subjective experiences.

Curator of the exhibition is Tatiana Kochubinska.

Evgeny Pavlov’s “Eclipse” showcased in the first room would be perceived as an introduction. The photograph features a group of people outlined in a square, and with each new image, this square gets darker, and the background lighter, until a state where only a blind spot remains. This is the way we perceive photographs of our parents that were made to memorise a travel to visit Moscow, or student works at a kolkhoz for instance: memory gradually gets used and erased, and there is no sense to attempt documenting one’s states.

The show starts with photo documents of the action “They’ll Settle the Score with Us for It” by Leonid Voitsekhov. In 1984, a hurricane rushed on Odessa that destroyed part of the city infrastructure. In reaction to it, artists held an action in which they called upon an abstract “somebody” to be held responsible for the destruction. This menace targeting the void as a way of conceptualising one’s own impotence and inability to control his or her fate whereas “they” should be held responsible for all disasters is an abstract substance that lives in a man’s consciousness as something that is adverse to him.

Next to it, is the photo series by Oleksandr Chekmenev as one of options of an answer to the question who They are: people whom we virtually never notice in reality. The series “Passport” was created in Luhansk in mid 1990s, at the moment when new Ukrainian specimens came to replace old soviet IDs. The photographer documented the process of photographing people who are not able to leave home due to health reasons. The photographs show awful everyday conditions in which they live and disgust of social workers who are in reality part of the same social level. Having become part of an independent democratic country these “they” still remain part of a ghetto that is established in a natural way in any society.

Then, a visitor discovers the honour board: the place where only leaders and those who have succeeded to outshine the crowd in some competences and become a visible Personality deserve being featured. In the soviet time, a chance to see one’s photo on an honour board could serve as a strong motivation to work. This being said, for older generation people, this would be sufficient to feel their success. However, Zhanna Kadyrova’s work features only one same person: the artist herself. With her natural feel of self-irony, Kadyrova disguises in various character types. This always looks funny indeed to watch how much importance simple people give to catch an opportunity to outshine others and live their 15 minutes of glory. On the one hand, the artist shows how awkward we look in this race, and on the other hand, how to devaluate attributes of success from the past.

The work “Gratitude” by Sergei Anufriev continues the theme of uncertainty and lack of self-identity. Such letters of gratitude used to be granted as an incentive, but today these certificates look like an implicit rebuke. The “unspeakable” and “extraordinary” gratitude are words that mean nothing and contain neither qualitative nor quantitative definitions.

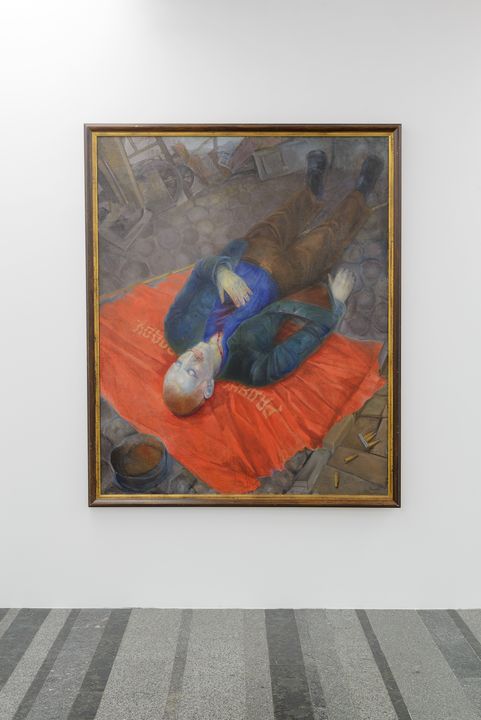

In the first part of the show, we see that attempts to make everybody equal have lead to a total depersonalisation. This is a story where it is impossible to see a difference between before and after. Anonymity provokes a feeling of amorphousness, and Viktor Palmov’s painting “For the Soviet Power” (1927) featuring a dead revolutionist lying on a red flag is perceived as an affirmation mark, and death here is an inevitable outcome and the only thing that provokes no doubt.

In the video by Serhiy Popov featuring protesters demolishing a Lenin monument, a notional shift occurs when the crowd defeats old idols by breaking it into souvenirs. What is the danger that a piece of stone shaped by a sculptor contains? In its essence, this action is absolutely rational, but it is obvious that this collective ritual contains a power of effect on masses, revealing profound instincts of the man.

Oleksandr Roytburd’s three-channel video “Balkan Ritual Music” generates a mystic and somewhat terrifying atmosphere: the same feeling as superstitions and religious ceremonies provoke. Primitive instincts of the man that are difficult to rid of are revealed again here. All one can do is only sublimate. The image of a man with a monkey’s head characterises clearly the modern society whose thoughts seek to satisfy animality, regardless of all intellectual and technologic achievements of the mankind.

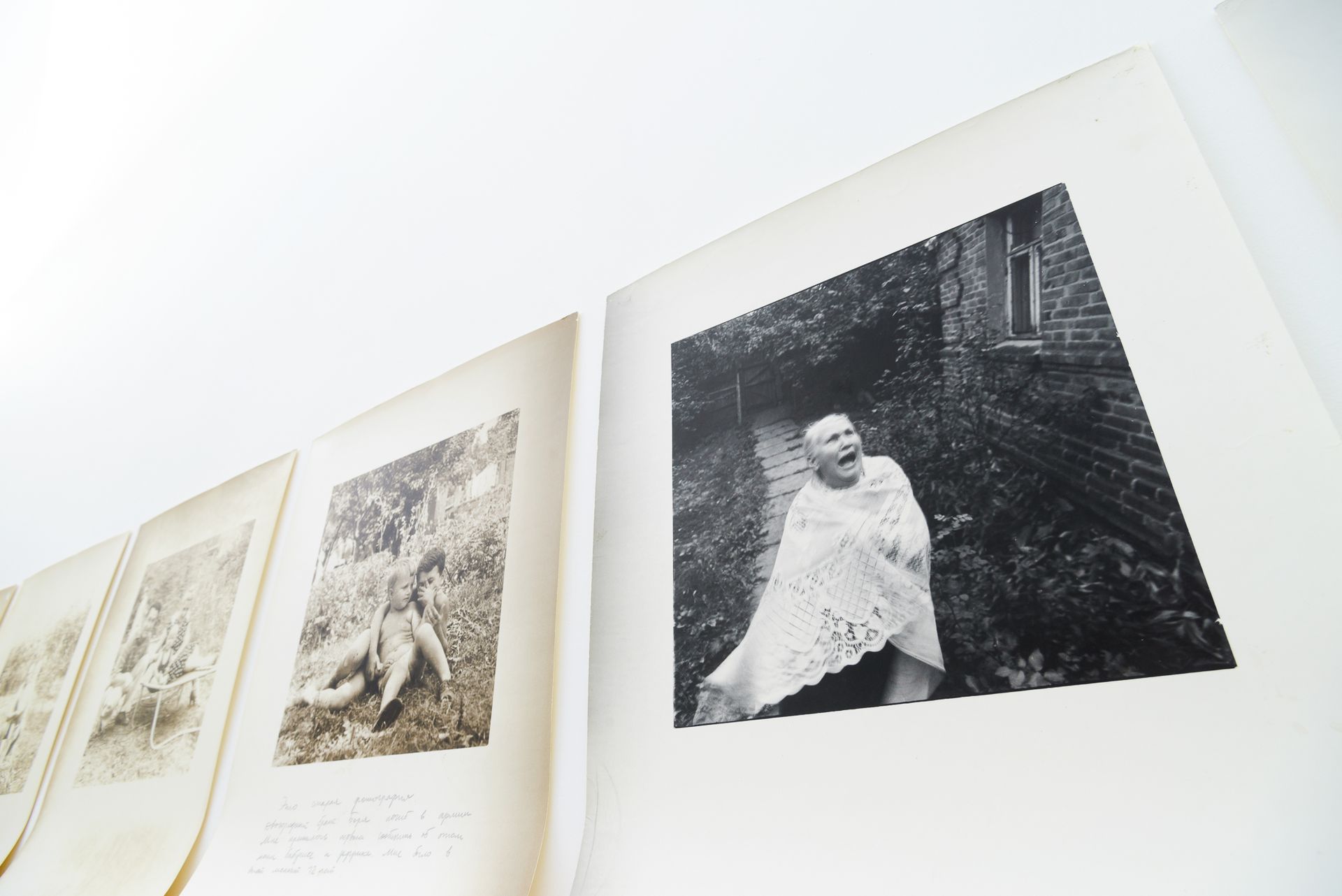

After the “Balkan Ritual Music”, there is a room with works by Sergey Bratkov, Kirill Protsenko and Vasyl Tsagolov: it feels so spacious and bright that it provokes a feeling of relief. This room is kind of an appendix in the overall show: it reminds of a pantry where all memories of the childhood, about family and friends, about places that used to make feel good are stored. Bratkov’s series, “No Paradise”, is dedicated to the author’s parents’ garden. The photographs are complemented by memories about life of the family at their countryside house. Flecks of sunlight in sepia, cosy interiors, parents’ portraits, short notes about events that are of importance only to members of this family, this is the form in which our memories about the past exist. However, all most touching moments are always surprised by death, broken destinies, pitiless reality one cannot hide from.

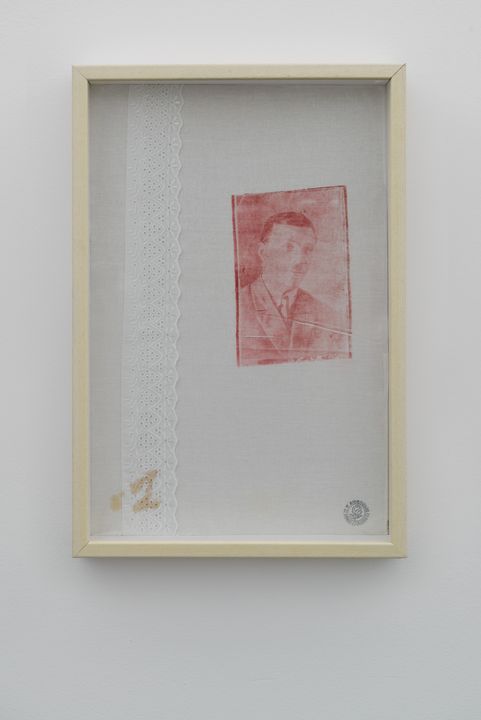

Kirill Protsenko’s “White Spots” symbolises a certain “social consummation”. The red colour of prints draws parallels to blood on bed sheets during the first wedding night, and the shape of spots reminds of soviet stamps on bed-clothes, textiles and anything that was in communal possessing.

The society has a unique faculty to remain unchanged in its essence, yet undergoing continuous transformations at the same time. In her video, “Leader’s Favourite Toys”, Oksana Chepelyk raises the major questions that our generation is concerned about: gender, sexuality, totalitarianism, web technologies, scientific progress and politics. The artist disguises as Lenin, Hitler and Einstein, using “spare parts” of fluffy toys as a finishing element of her characters: for example, a teddy bear’s ear used as Hitler’s moustache or a dog’s scalp used as Einstein’s haircut. The video is complemented by quotes about children’s sexuality from Freud’s “Three Essays”, since, as it is known, all preferences are formed in childhood. The second part of the work is video documenting of the interactive installation “Piece of Shit” where the artist had composed the word “Policy” using elk excrements: a metaphor saying that politics is a dirty business. When the participants changed one letter, they came up with the word “Police”. In between, various words starting with W turn up, but the key words are “war” and “web”. Now, there is place for a new format of warfare, provided by the global web network, and this war is as destructive. The work was created in 1998, and it integrates all the fears of the society that, 20 years later, still remains frustrated.

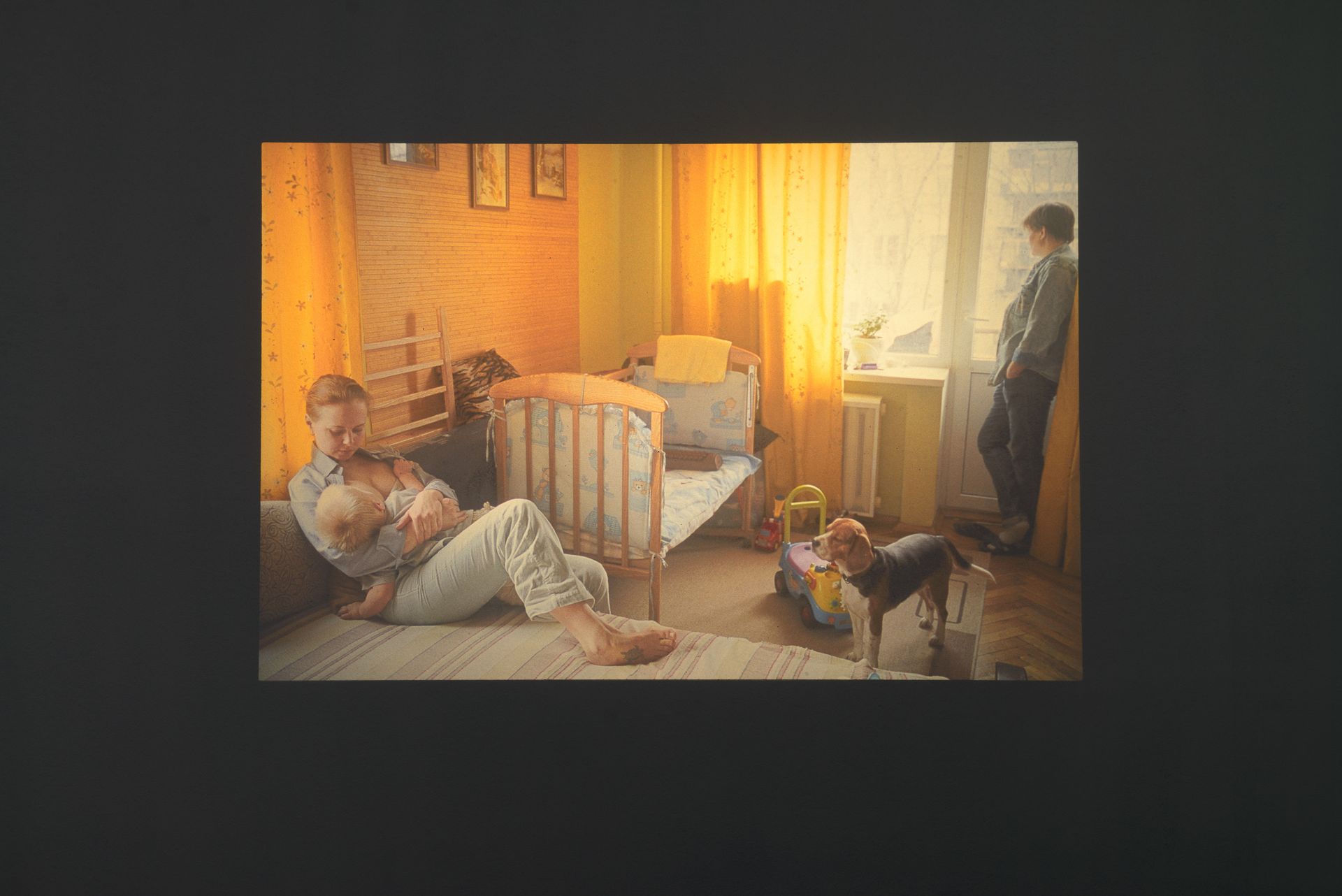

The next room showcases two series of photographs: Roman Pyatkovka’s “Adultery” featuring a poligamic alliance of two women and one man, and Yevgenia Belorusets’ “A Room of My Own” dedicated to life of LGBT couples. Showing intimate sides of a man’s life allows examining the “anonymous society” kind of under a microscope, revealing all of its components.

When the issue of acceptable types of relationships starts being debated, this is only a sign that in reality, there is no personal state. Even an apartment’s door that is locked cannot separate you from the society. One way or another, life still flows within the society, and what makes difference is only the way in which this interaction happens: in denial or in acceptance.