Exhibition of shortlisted artists for the PinchukArtCentre Prize 2018

The PinchukArtCentre (Kyiv, Ukraine) presents the exhibition of 20 shortlisted artists for the fifth edition of the PinchukArtCentre Prize, a nationwide prize for Ukrainian artists younger than 35. The show focuses on the presentation of new works, produced with the support of the PinchukArtCentre.

The exhibition brings together a group of artists from an unprecedented variety of regions, coming from all over Ukraine including artists living abroad. The range of subjects in the exhibition is wide. Some artists deal with socio-political narratives of Ukraine as a country in conflict and the impact on its people. Others draw from self-exploration through the use of material, form and media. A third common subject in some of the shortlisted positions is the search towards future and the constructions of utopias.

“With the 5th edition, we celebrate 10 years of the PinchukArtCentre Prize supporting and enabling a new generation of Ukrainian artists. After so many years, having welcomed so many artists, I can only be proud to observe a radically new generation of artists coming to the art scene. Their concerns, language, and subjects are different; they announce a new way of thinking and a new way of showing what Ukrainian art could be for the future.”

The 20 nominees for the PinchukArtCentre Prize 2018 were shortlisted by an independent Selection Committee from more than 650 applicants and include: Mykhailo Alekseienko (27, Kyiv), Iuliana Golub (27, Kharkiv), Taras Kamennoi (32, Kharkiv), Mykola Karabinovych (29, Odessa), Pavlo Khailo (29, Lugansk/Kyiv), Alina Kleitman (26, Kharkiv), Vitalii Kokhan (30, Sumy/Kharkiv), Yulia Krivich (29, Dnipro), Sasha Kurmaz (30, Kyiv), Larion Lozovyi (29, Kyiv), Roman Mikhaylov (28, Kharkiv/Kyiv), Oleg Perkowsky (33, Kamianets-Podilskyi/Lviv), Sergii Radkevych (30, Lutsk/Lviv), Yevgen Samborsky (33, Ivano-Frankivsk/Kyiv), Dmytro Starusiev (32, Makiivka), Ivan Svitlychnyi(28, Kharkiv/Kyiv), Kateryna Yermolaeva (32, Donetsk/Kyiv), Anna Zvyagintseva (30, Dnipro/Kyiv) and groups: Yarema Malashchuk (24, Kolomiya/Kyiv) and Roman Himey (25, Kolomiya/Kyiv), Revkovskiy and Rachinskiy (Daniil Revkovskiy,24, Kharkiv; Andrij Novikov, 27, Kharkiv).

The exhibition of the PinchukArtCentre Prize 2018 is curated by Tatiana Kochubinska,PinchukArtCentre’s Research Platform curator.

The winners of the Prize will be announced at the award ceremony in April, 2018. A distinguished international jury will award the Main Prize of UAH 250 000 and two Special Prizes of UAH 60 000 each. In addition, the winners will each have an internship in studios of the world’s leading artists. A Public Choice winner will be determined by votes of the visitors attending the exhibition of the shortlisted artists and will be awarded UAH 25 000.

Future Generation Art Prize 2019 – an international art prize for young artists, established by the Victor Pinchuk Foundation in 2009.

The exhibition will be open from February 24 until May 13, 2018in the PinchukArtCentre, Kyiv, Ukraine. Opening hours: from Tuesday through Sunday from 12 noon to 9 pm. Admission is free.

The PinchukArtCentre Prize is a biannual prize awarded to the best Ukrainian artists younger than 35, launched in 2008. Funded by the Victor Pinchuk Foundation, it is aimed at fostering, supporting and developing a new generation of young Ukrainian artists.

Yevgen Samborsky works closely with people from outside the art milieu, and gets them involved in art processes. This practice bears upon relational aesthetics: the artist sets up a context and serves as a moderator who invites other persons to participate.

The exposition showcases Yevgen Samborsky’s experience of creative collaboration with various at-risk groups: children from the center of social and psychological rehabilitation, psychiatric ward inmates, and Roma settlements. As the result of each interaction, the artist and his interlocutors create paintings, drawings or sculptures together. The artist records these collaborations in his documentary films. Each collaborative act becomes an opportunity to explore himself and other people, highlighting human fragility.

The artist resorts to this practice by inviting his father, an alienated man with few social ties, to create art together. The father and son create a sculpture of the father as a young man. Shared experience and participatory practice that the artist has used as therapy for others help him to overcome his own childhood traumas.

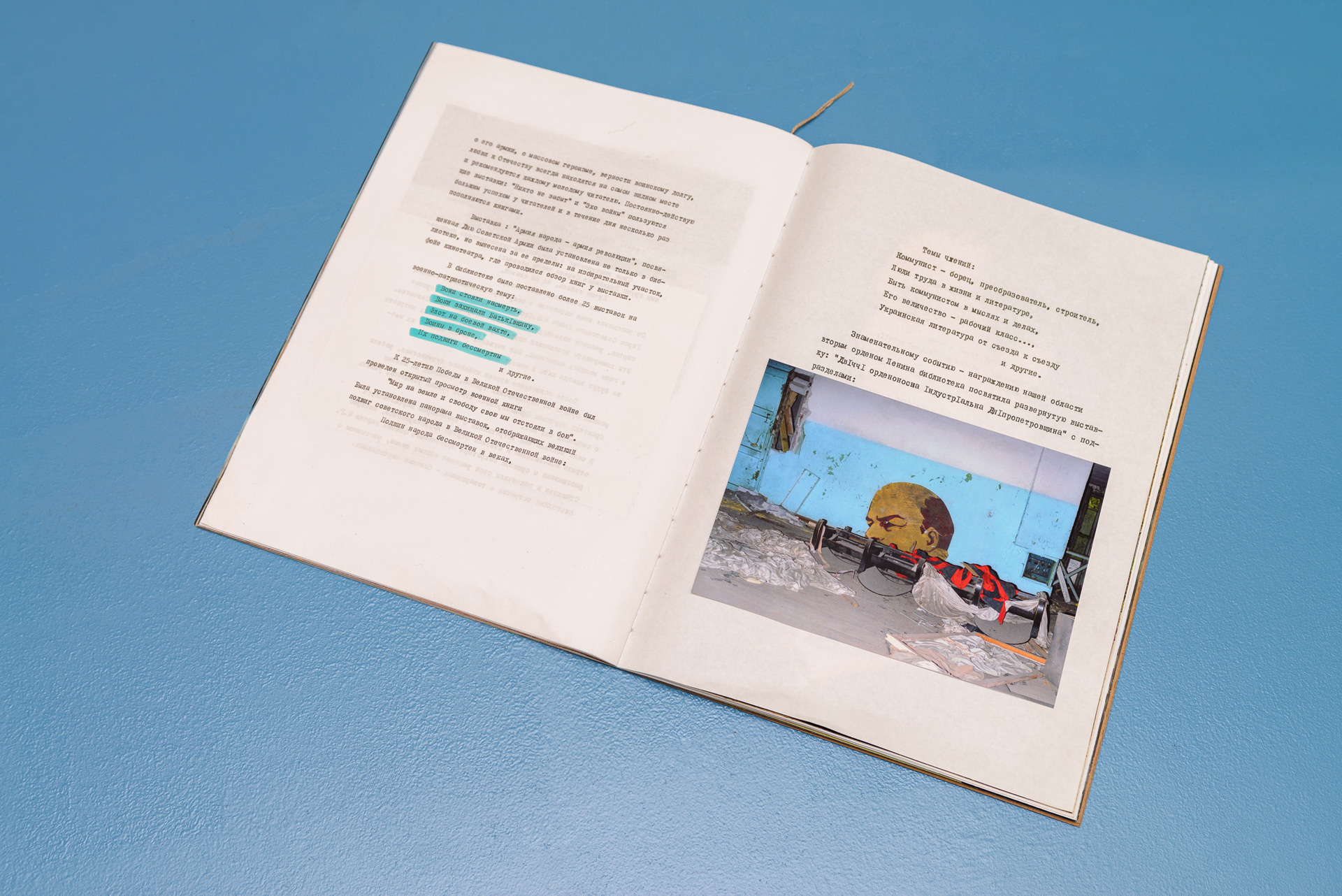

The title of the Daring Youth series that Yulia Krivich has been working on since 2015 refers to an eponymous hooligan gang she met a few years ago. The young people in the photographs are hoolies, war veterans and political activists of the right-wing movement, and yet they belong to the globalized youth culture: they travel, party, ride their bikes, and curate their image on social networks, including Instagram, which has become an instrument of self-promotion.

In the exposition, the series is united with an art book inspired by library records found in the library of the Ilyich Palace of Culture (Dnipro), documenting Leninist propaganda among the youth. Using the library record as her starting point, the artist creates an art book that unites her own photographs, snapshots from “her protagonists’” Instagram accounts, and slogans from the log, juxtaposing Soviet and present-day instruments of propaganda.

Mykhailo Alekseienko bases his creative practice on the principles close to relational aesthetics: the viewers’ direct participation is an integral part of an artwork.

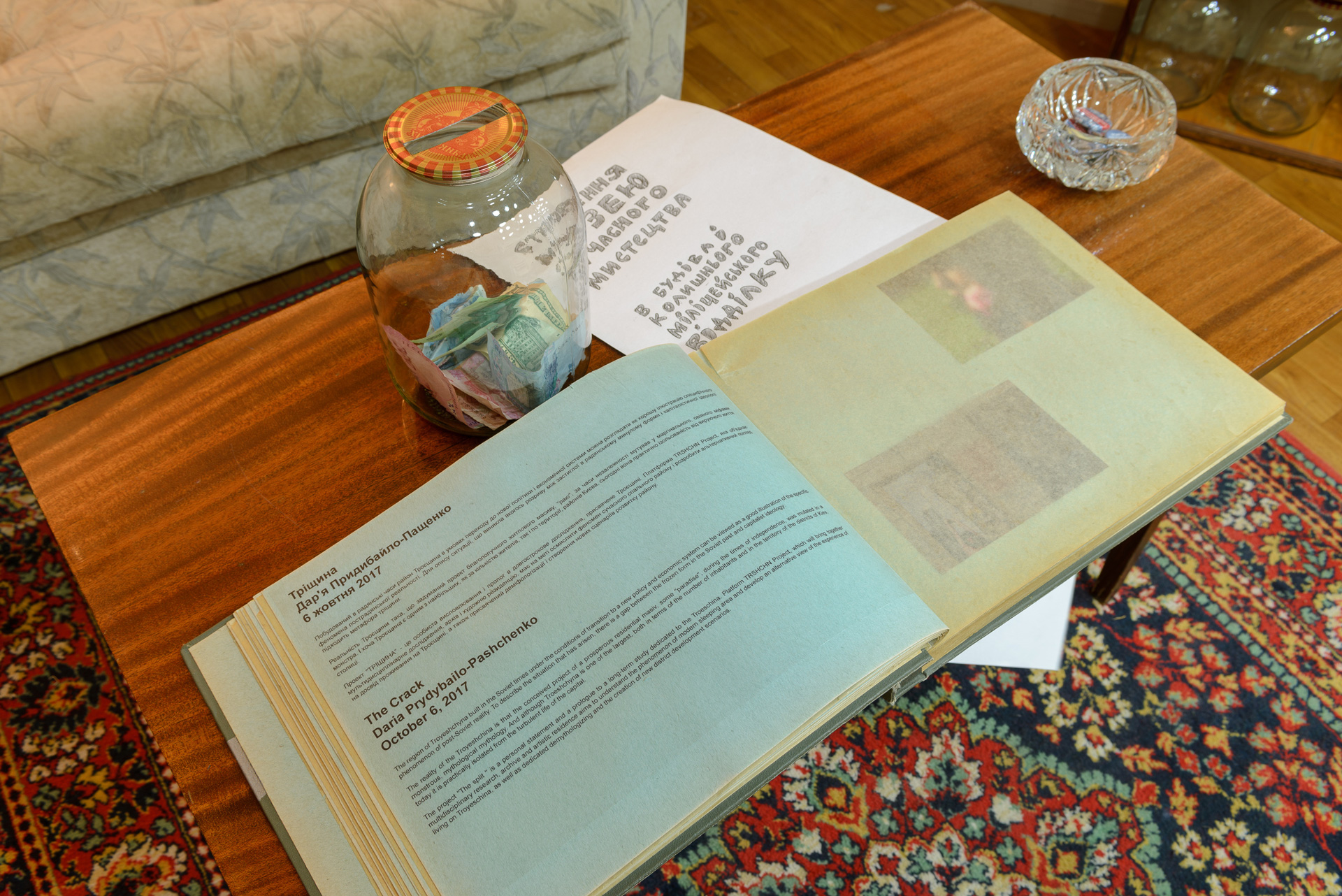

Startup Troeschyna is a long-term project geared primarily towards fundraising for cultural initiatives. Its goals include the development of the Apartment 14 independent art space that the artist created in his own 2-bedroom apartment in the Kyiv suburb of Troeschyna. The apartment formerly belonged to his grandma, whose room remained untouched after her death. From 2016 onwards, the initiative was sustained by the enthusiasm and financial support of other artists. Alekseienko wants to raise 200,000 hryvnias (approximately $7,400) with his Startup Troeschyna as the seed fund for developing cultural initiatives in the city’s residential district. The costs will support the decentralization of art processes, overcome existing stereotypes about the district of Troeschyna, and foster neighborly ties between district residents.

The project’s logo is based on a sculpture entitled Bird House as a symbol of Troeschyna, and as a metaphor for the constructive power of the collective.

Each viewer who chooses to support the initiative will receive a small gift.

Reward tiers include:

- 20 UAH – a unique postcard

- 50 UAH – magnets designed by the artist

- 100 UAH – a set of postcards from exhibitions in Apartment 14

- 250 UAH – a personal sketch by Mykhailo Alekseienko

- 600 UAH – a personal watercolor by Mykhailo Alekseienko

- 1000 UAH – Mykhailo Alekseienko will create a unique portrait of yourself to be exhibited at the exposition (contact the mediator for details)

Vitaliy Kohan’s art practice is recognizable in its poetics, a haptic quality and attention to materials as both the subject of his works, and their expressive means. The artist explores how an image turns into expression, and vice versa, when a random object gains expressive properties. Kohan subjects the items featured in the exposition to his “para-scientific” experiments evocative of experiments in physics classes. These objects document the “behavior” of elemental natural processes. Large-scope compositions that demonstrate the influence of light, fire and water coexist with real-time video projection of a crystal growing. This draws our attention to fluidity, impossibility of cohesive perception, and manifestations of the intangible.

Mykola Karabinovych often combines his personal experience with explorations of various musical genres, including folk music, and provokes other artists to create new works.

In his work entitled The Voice of the Delicate Silence, Karabinovych addresses the tragic history of repressions, deportations, sadness, mourning, and sacrifices through the lens of his family history. The artist’s great-grandfather, an ethnic Greek, was arrested and deported to Kazakhstan in 1949, where he died 5 years later.

The search for information and his father’s memories about his grandfather reminded Karabinovych of “rebetiko,” a Greek music genre that emerged in Athens in the 1930s and is strongly associated with persons relocated from Asia Minor. In The Voice of the Delicate Silence, Karabinovych asked the musician Yuriy Gurzhy to create a rebetiko song, and traveled to the town of Shelek (formerly Chilik) in Kazakhstan to install a symbolic monument to victims of repressions. The monument is a loudspeaker that broadcasts a piercing mourning song over the silent Kazakh steppe.

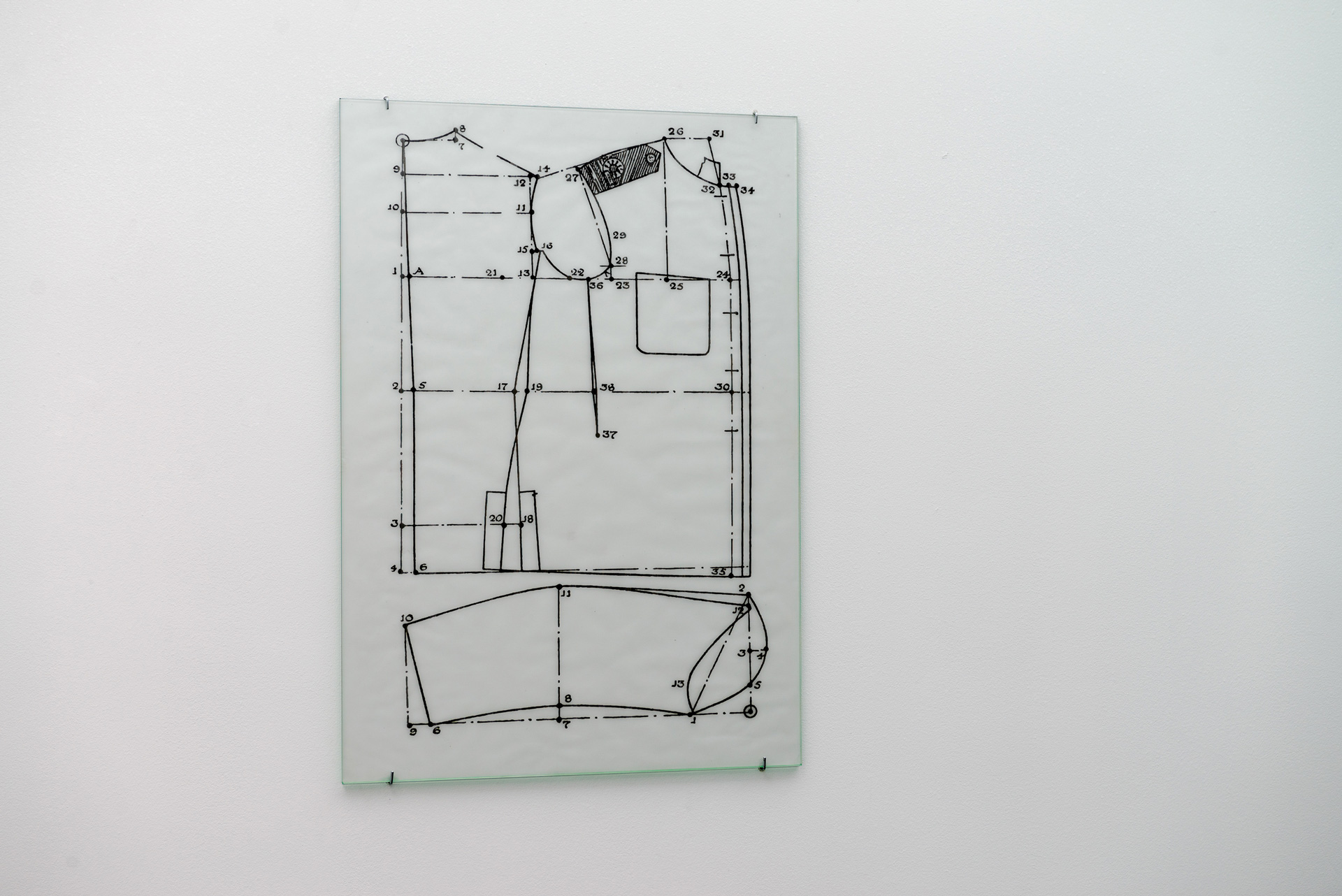

Serhiy Radkevych tests the communicative potential of sacred art, including iconographic paintings, in the contemporary world. His Monument to the Victims, based on patterns for military uniforms, creates a voluminous spatial form stripped of its initial function and attributes of aggression. By elevating military uniforms to the level of an abstract symbol of a human body, Radkevych demonstrates the absurdity of violence.

The work Ethical Spot harkens back to the “exhibition” the artist organized at the construction site he worked at outside his hours. The construction crew became the exhibition’s first viewers. The artist was tasked with clearing construction waste from the territory temporarily provided by the site’s neighbors free of charge. Kamennoi dug up the plot, making manifest the real and previously invisible borders of the adjacent territories. The outlines of the freshly dug up earth created a new plot as a metaphor of the “new” no man’s land.

In his work for the PinchukArtCentre, Kamennoi created a monumental installation that recreated the shape of that territory. The exposition also features the artist’s drawings of his quotidian asocial life at the construction site, its blueprints and photo documentation.

Kamennoi’s gesture at the construction site, which pays lip service to one citizen’s respect for the other, and the present installation allow the artist to deliberate the concept of territorial integrity.

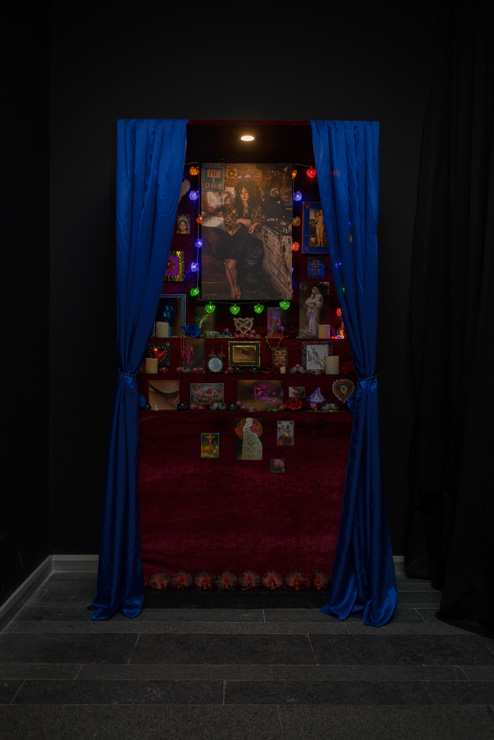

In her new work Me, Myself, and I, Katerina Yermolaeva continues to develop her multiple male and female avatars. The artist develops a behavioral pattern and look for each character. These images combine typical human personalities with the artist’s personal fears and experiences. Driven by a search for her alter ego, Yermolaeva creates nine stories describing various characters as her subpersonalities. Taken together, they create an ideal community, a perfect world comprised of her various selves, from the quintessential good girl to a valiant knight or party animals.

Revision of Rules is a game model for a quintessential game, a pattern for gaming a game, so to speak. Its participants (white-collar workers) dictate the rules of economic games to the viewers, and invite the viewers to discuss the rules without changing them. At the same time, their actions in space are defined by the rules they have established for one another.

Agreement to follow the rules is the basic precondition of any game’s success. In point of fact, the option of discussing the rules is the basic difference between the game space and the quotidian space, where the rules are intuitively understood and dispersed in all processes to the point of being bracketed out of the space of discussion. Besides, game-like interactions provide key algorithms of engagement and motivation in the present-day economic and political reality. Gamification blurs the line between games and not-games, transforming playing from a liberating practice into yet another instrument of economic subjugation.

These instruments are created by white-collar workers (advertisers, communication specialists, IT workers, etc.), or, to resort to the term coined by Franco Bifo Berardi, “the cognitariat.” Contemporary economics demand creative output of them, and yet their output is not supposed to undermine the status quo. The conditions that resist problematization remain invisible. As the result, the energy and intellectual potential of the cognitariat are redirected towards creating new elements within the set parameters, defusing their knowledge as a potential agent of radical change.

In Reviewing the Rules, the participants engage in a daring experiment: they play themselves, albeit alienated by the exhibition space. The very term “performance” here gains an economic dimension, referring to productivity and efficiency rather than spectacle. For the participants, it is both a game (a possibility of new experience that allows to shed the routine) and work (an element of their day-to-day work schedule and a source of income).

In his work No Game — No Hero, Roman Mykhailov continues to develop the image introduced in his series of paintings Fear. The running man emerges as the central image of the series. In the new work, Mykhailov focuses on the image of his protagonist in the contemporary world, where trends got supplanted by hypes, and the protagonist, or the prophet, to be more precise, is given to doubt. The artist invites the viewers to explore the issue further by offering that they don the role of either the protagonist or the antagonist. The game’s script, however, has only two behavioral models: you either flee or chase.

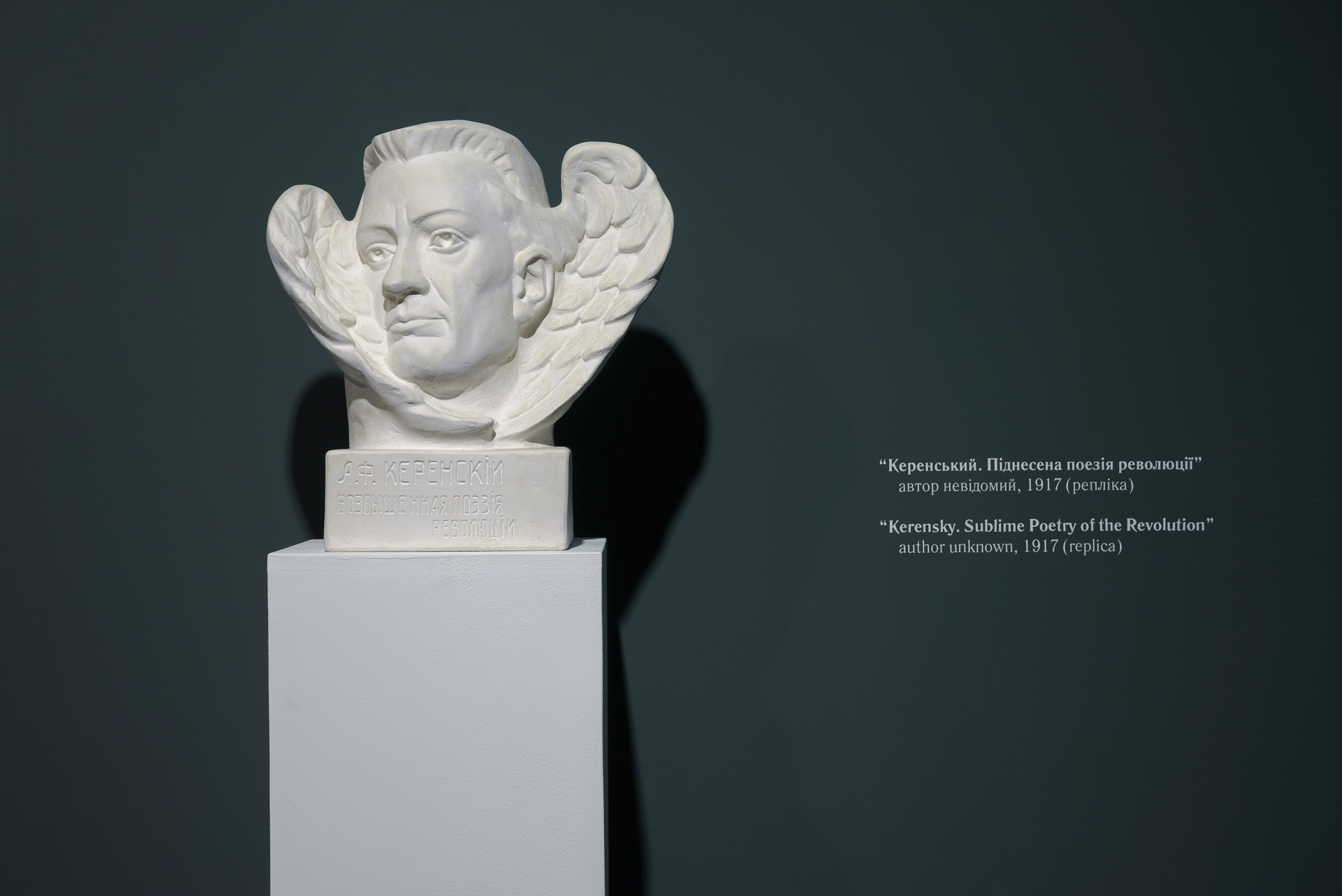

Larion Lozovyi pays particular attention to ties between artistic and historical phenomena. In his Beetroot Revolution, he continues to develop his methodology of artistic study. He engages with the materials connected to the revolutionary processes of 1917 to construct an archive of an imaginary event. Long before the Bolshevik Revolution, the February Democratic Revolution culminated from the hopes of millions citizens. And yet, it also demonstrated that the product of a revolutionary act can be appropriated by the forces inimical to the original emancipatory agenda. It provided examples of mass consumption of the revolutionary image commissioned by the new authority (the Temporary Government). The commission was to be met by art communities trying to adapt to the changes. Under the conditions, the artistic avant-garde proved dependent on the goodwill of politicians and the big capital, and all criticism was defused by the context that produced it. Lozovyi’s fictitious Beetroot Revolution is a metaphor of the phenomena defining our era, namely, the cultural industry and political populism. We can take a closer look at them by examining archival objects, edited video footage and audio guides to the hall.

In his art practice, Dmytro Starusiev engages with analogue photographic processes, with their sense of unpredictability, tactility and handmade character that allow the viewer to perceive each work as a physical object. The documentation of the emotional dimension of reality, as expressed in abstract compositions and expressed through the medium of photography, is of primary importance to the artist.

The artist creates large-scale analogue photographs in museum-style frames, actualizing the discussion about the very essence of the photographic medium and its autonomy. He breaks it free of the canons and stereotypes that guided it previously. He seems to affirm the prognosis voiced in The Dictionary of Received Ideas by Gustave Flaubert, namely, that daguerreotype will “replace painting.” A photographic canvas is perceived as a painting, and the properties of analogue photography emancipate it from its function of documenting reality, creating sensuous liminal images that marginalize the object and foreground experience as such instead.

The idea of the Three Sisters’ Story series first emerged when the artist stood on the border of three states: Ukraine, Russia and Belarus. These works combine low fleshly experience (mutilated bodies, chopped innards, new life sprouting from empty, scooped out voids) with religious awe, the elevated sense of reverence, wonder and fear at something beyond words and touch, something lofty and important. These images are evocative of the Biblical “the windows of heaven were opened” and reflect on the beginning and the end, the nonexistence and existence beyond time. Large-format photographs are constituted of two parts: a product of a purely technological limitation, these sutures are evocative of scarred human flesh, mutilated vaginas, abutting borders and territories.

The title of The Chronicle of Current Events by Sasha Kurmaz refers to the eponymous Soviet civil rights bulletin that circulated through samizdat. Kurmaz presents a total installation richly saturated with various media and allusions. When entering the space, the viewer is confronted with the statement “Your sacrifice was in vain,” a result of the performance the artist organized on January 22, 2018, in an abandoned cemetery in Kyiv. The exposition develops through political and socio-cultural juxtapositions.

The hall showcases the photographic series 12 Months: the 12 works reflect the monthly chronology of losses of Ukrainian military in Eastern Ukraine over the course of 2017. The series coexists with a photograph of the destroyed composition entitled Communism Is Our Goal on the wall of a school in the village of Volodkova Divytsia (formerly Chervoni Partyzany) in the Chernihiv Region, a four-channel video collage State of Emergency, cut from created and found footage, and the looped video I No Longer Dream.

Alongside these, the exposition features the print run of the book Heaven, which documents the city’s nightlife: against the backdrop of political and economic crisis, techno and house parties might be the only space in Kyiv that has the potential to unite the youth regardless of their ethnicity or political orientation. Rave becomes an alternative world in which people develop new types of relations while simultaneously calling for peace.

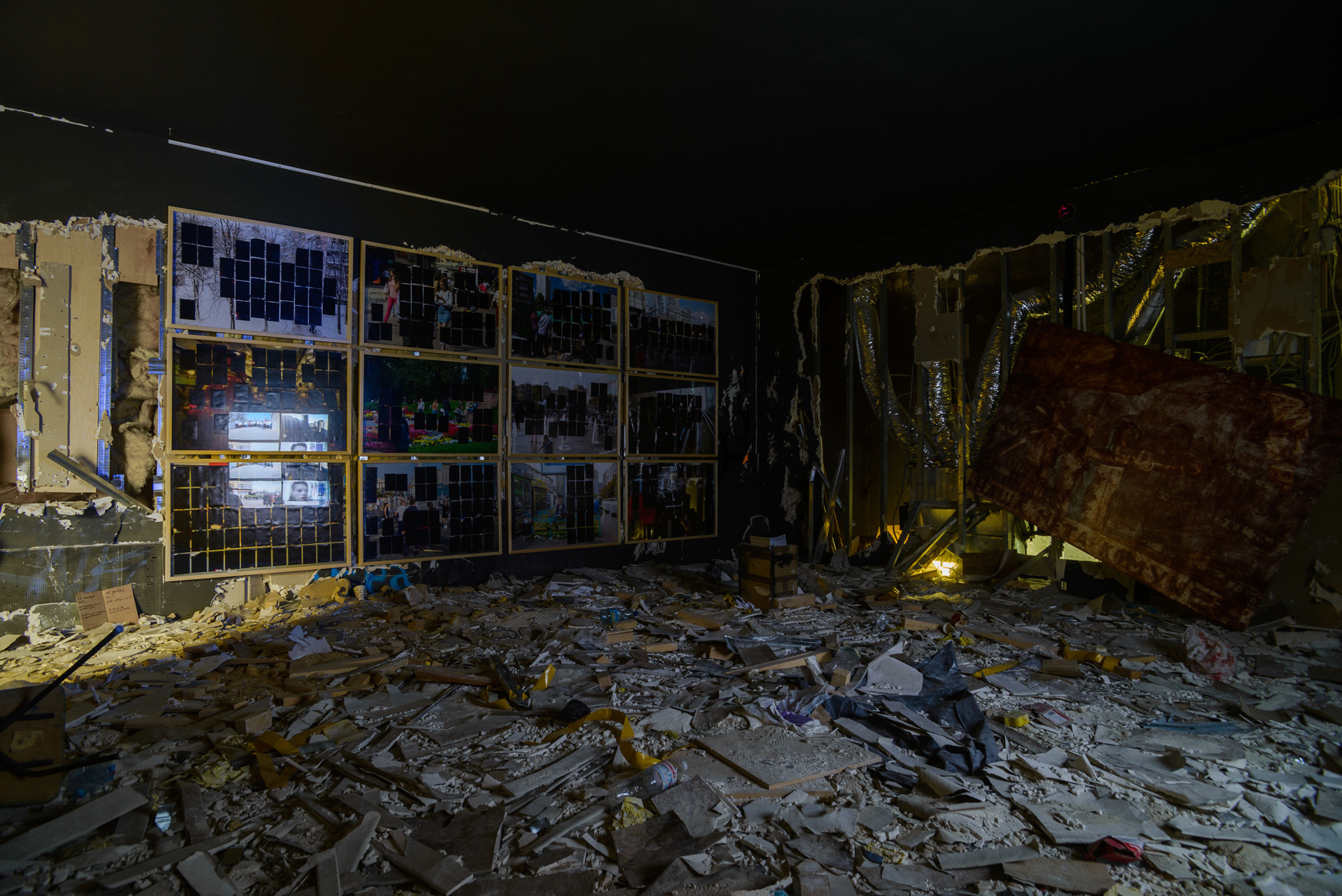

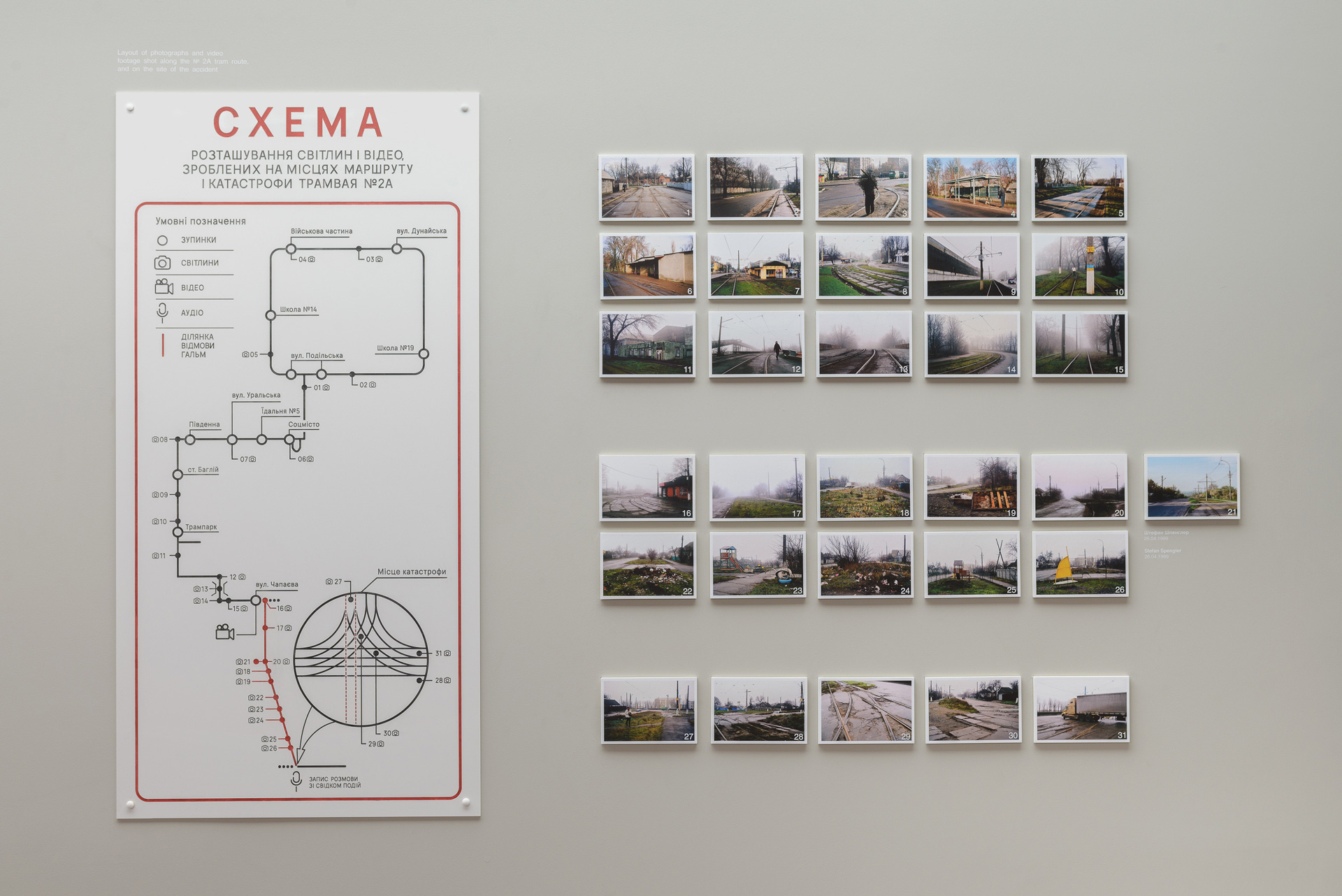

In their art, Daniil Revkovskiy and Andrii Rachinskiy engage with social problems and introduce the strategies associated with investigative journalism. Their works reimagine found and collected footage provided by the urban environment and social networks.

The tragedy that happened in 1996 in the city of Dniprodzerzhynsk (now Kamianske) was their starting point. A KTM-5 tram running along the № 2а route suffered a braking system failure at the steep slope, resulting in the deaths of 34 persons, and in injuries to more than 100. The story inspired the artists to conduct an investigation that uncovered deeper social problems. A local tragedy highlighted the human habit and gift of conformism.

Iuliana Holub’s Algorithmic Family is a real-time video simulation. The artist wrote an algorithm guiding the simulation to analyze the news items incoming from news sites in real time, and the protagonists of the Algorithmic Family react to them. Their reactions are expressed through movements, sounds (grumbling, laughter, crying), verbal phrases, or melodies. The characters can express eight basic emotions (anger, fear, joy, sadness, annoyance, agitation, inspiration, and indifference). Their entire life is guided by news, random coincidences and algorithms.

The artist has placed the family in the kitchen, the space associated with private uncensored conversations since the Soviet days. In this work, Holub demonstrates the effect the media have on a regular family in the present continuous information stream, when media consumption reaches absurd levels. Free access to information does not guarantee its veracity, and reactions to it do not transcend private spaces.

In her work Ask A Mom, Alina Kleitman addresses childhood fears, phobias and experiences. The artist plunges the viewers into suspense, forcing them to wander the labyrinth of various feelings, from fear to reproach. In multiple video projections, Kleitman monumentalizes body parts, underscores gestures that are demonstrative, mentorly or oppressive in nature, and invites the viewers to traverse all circles of hell of childhood fears and memories.

The title in To Whom Have Thou Abandon Us, Our Father? by Iarema Malashchuk and Roman Himey takes a line from the choral part of the people in the first scene of the prologue to the opera Boris Godunov by Modest Mussorgsky. The image of “the people” is central to the film. The choristers of the Chernihiv District Philharmonic as they go to work are the movie’s protagonists. The artists documented their day-to-day work life and the time before recitals. The camera follows them, singling out quotidian scenes evocative of monotonous factory work. The impression is further underscored by a bell that punctuates the plot’s unfolding. In the final scene of the film, the protagonists sing the choral part of the opera, make it sound deeply personal. Their appeal to “the lessons of the past” maps onto present-day political realities, demonstrating “the scenery” that the country has found itself in. The film offers a critical perspective on the antiquated image of the dispossessed nation.

In her works, Anna Zvyagintseva often focuses on elusive, barely perceptible moments from our quotidian life. The exposition features three works united by the idea of automatic writing. A collective drawing produced by unconscious collective actions over time (traces of hands touching the handrails, cigarettes snuffed out on the wall, etc.) captivate the artist both as a collective artwork and as an expressive utterance that does not use any medium in particular. Drawing occupies the central position in Zvyagintseva’s art practice, undergoing transformations through the introduction of various materials. It is also often pulled out of the 2-dimensional surface to create spatial voluminous objects. The works are constantly changed through repeated monotonous actions spread in time. A white surface used as a “basis” for a voluminous graphite drawing in the exposition is undergoing constant transformations: it is erased and muddied, and its texture changes with direct input from the viewers.

Ivan Svitlychnyi’s Script is the first part of a trilogy. It follows in real time the formation of an algorithmic scenario for a future performance, and lays the foundations for its visual and audial shape. The script processes the data obtained through an analysis of low level Internet protocols by the servers located in various places around the globe. The data received is framed as a stylized mold of social connections between humans, and is visualized as virtual reality.

The script is based on in-depth analysis of human nature, including its biochemical, physical, technological, and social dimensions. The biomaterial “aspect” of mankind is emblematized by microorganismic colonies cultivated in Petri dishes. The shape of new anthropology is expressed through data analysis. Data streams, as well as transformations and developments of colonies, are visualized on screens in real time. Moving images from the colonies are processed as sounds.

The artist observes that, at its present stage, humankind is facing unpredicted challenges, and raises the question of what will come to define the status of an artwork in the future, how we will perceive our surroundings, what our priorities might become, what will define the new visuality of the future, and invites his viewers into hypervisuality with this work.

In his work Synchronizing the Present, Oleg Perkowsky addresses the issue of time, and the possibility of documenting the moment. He realizes this idea through the image of an ongoing construction site. The exposition focuses on the slide projection of photographs of unfinished buildings in the city of Uzhhorod and on its outskirts, appearing as completed objects within the framework of the architectural rhythm of the streets and landscapes. The artist strips the images of ongoing construction sites of all social and political contexts, foregrounding reflections on the position of an individual in the Universe in the period of constant acceleration. By observing ongoing construction sites, the artist seems to invite us to slow down and come in sync with the earthly nature in its present state

PinchukArtCentre Prize 2018 Award Ceremony