“Volova’s facet of national post-clecticism” (“Between the Zusil of National Post-clecticism”) – an unwritten mystical program, as promoted by artists Oleg Tistol and Kostyantin Reunov in 1987 – on the evils of aesthetic, social and political changes in the SR SR. The creative ideas that formed the basis of the program emerged from the Mitzi during their stay at the military unit Makarov-1 near the Zhytomyr region, where both were serving in military service.

The essence of the program lay in the struggle for the beauty of the national stereotype. More precisely, the mystical strategy of the artists was described by Kostyantin Akinsha, who identified the creativity of Tistol and Reunov as a national art – a mystique that surzhik will follow: “Reunov and Tistol do not vikorize the stamps of national culture as much as their own This is a subculture that is characteristic of Ukraine, which can be defined as Surzhiku culture. […] Prote surzhik is not less than mov. This is a falsified history, rewritten with cliches, and a riot of national kitsch. This is a chestnut candle, and a girl in a wreath, and thousands of meters of canvas wasted by Kiev artists on the images of “Kiev sects”, and landscapes of “Malyovnych Ukraine” [1].

The term “national” is important for the overall creativity of the Mitzi, and even the myths and symbols of both the Ukrainian and Russian cultures (and also the Radian mass culture) formed the basis of their artistic language and formal poshukiv. Later, in an interview with Radio Liberty, Oleg Tistol said: “The word “national” was unusual there—not to be confused with nationalistic. We appreciate that we considered ourselves responsible for creating the so-called new cultural brand. It was surreptitious and at the same time serious. I stand for everything. […] I am very sensitive to nutrition – culture as a real process and culture as an imitation”[2].

Reunov, in his own words, explained: “As a new generation, we must create something new, and at a new price we are in a completely different level of imagery with quotations and the great world of eclecticism of different layers of culture of contemporary classical mystique, spiraling headlong into the classical pictorial way of expression . In connection with this, it is important to decipher the thesis “struggle for the beauty of a stereotype.” These diverse stereotypes of culture, as the most beautiful manifestations about those who are “beautiful” in the superlative of beauty, we can immediately recognize and, perhaps, create a completely new stereotype. The stereotype is like a compressed system of expectations of a new phenomenon and, apparently, a new mystery. On the one hand, the leather artist works with classical culture, and on the other, he brings from it new elements of form, expression, and also creates new manifestations”[3].

Kostyantyn Akinsha views the work of Tistol and Reunov as a revolution in Ukrainian mysticism. In addition, there is an ironic distinction between the concepts of the “Ukrainian wave” and the “Ukrainian wave”, which extends back to the first postmodernists, such as Savadov, Senchenko, Golosiy and Hnylitsky, who work from the overtones of European culture (talk about the Ukrainian version of the transavantgarde), and before others — “Vol’ovaya verge”, based on a local warehouse and robots with Ukrainian cultural codes. Since the “wave” had already formed, the “wave” at the time the article was written (1989) was rapidly beginning to take shape and develop.

The first robots, which can be taken into account, were created under the influence of these ideas, dating back to 1984 (the same rock Tistol had already turned to the project “National Pennies”) and 1987 (the first “post-clectic” robots of Reunov, followed by his ceratis there are canvases). The characteristic feature of both myths is the supernaturalism of symbols and myths. The pictures are literally bursting with everyday anecdotes, tales and guesses. One of the brightest themes of this period, which is relevant at the time of the political crisis in the Radyansky Union, is the Russian-Ukrainian newspapers. On the canvas by Kostyantin Reunov “Don’t judge the Peremozhtsy. To the Great Russian People before the Great Ukrainian People” (1988) depicts a Russian who, having drunk himself, fell to the ground, but does not dare to drink up to the last portion of alcohol. Reunov infused this theme picturesquely, depicting the hero from behind, turning his back to the gazer, and placing a label of Russian vodka over his head. In Tistol’s work, the most diverse theme of Russian-Ukrainian centenaries is embedded in the picturesque painting “Resurrection” (1988).

Reunion”

by Oleh Tistol, 1988

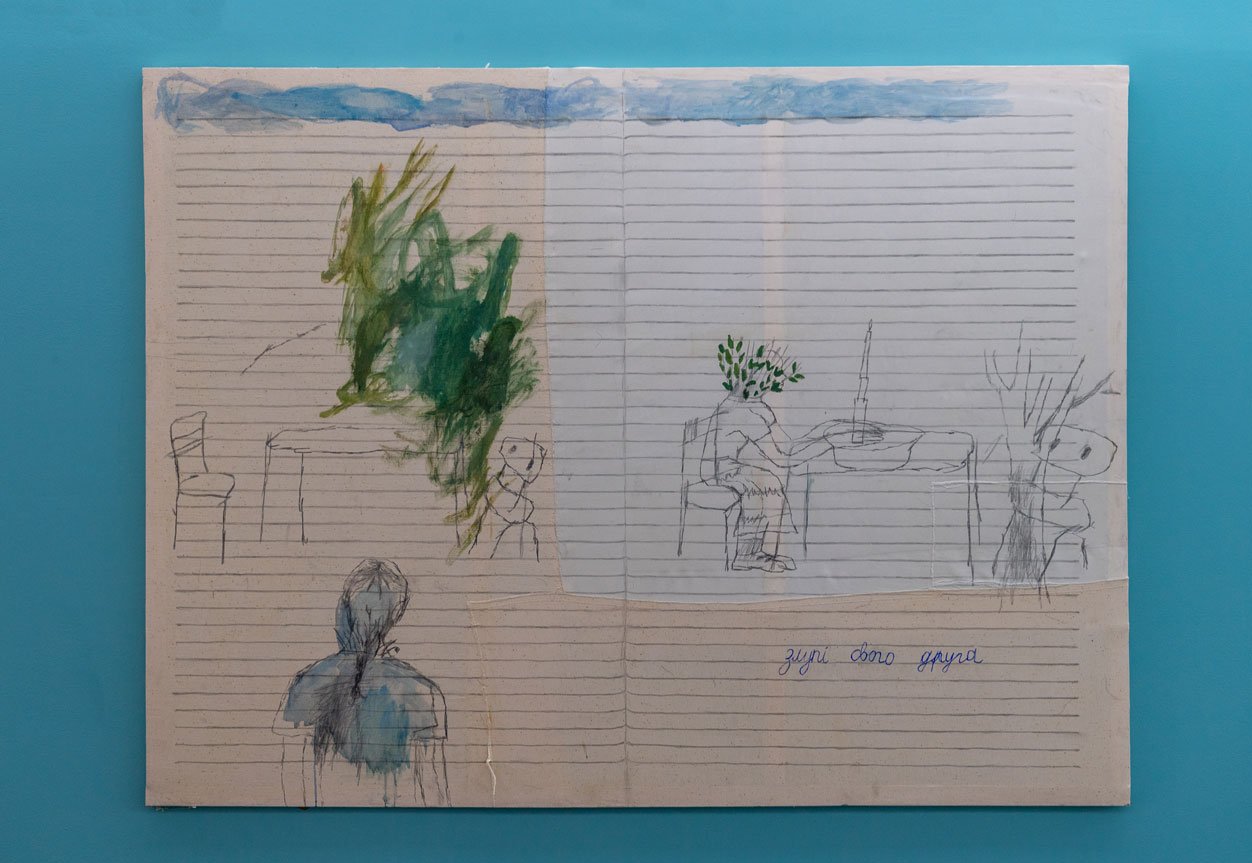

Reproduction of the work “Winners are not judged. To the great Russian people from the great Ukrainian people”

by Kostiantyn Reunov, 1988

Just as Reunov had a great vision for the images of pop art, Tistol drew inspiration from historical subjects, for example, delving into those of Ukrainian Cossackism. The attributes of the Cossacks themselves are numerous maces, Cossacks, horses, zhupans, slabs, which then correspond to the pictures with additional meanings. Traditional for Tistol’s creativity were those of historical health and union.

In 1987, a group of artists took part in the exhibition “Kiev-Tallinn”, and in fact for the first time in the Ukrainian SSR they showed their “post-clectic” ideas. The artists suffered the same fate at the Radian-American exhibition in Kiev.

At the end of the 1980s, together with artists Marina Skugareva and Yana Bistrova, Tistol and Reunov moved to a Moscow squat near Furmanny Provulok. Before them came a young artist from Mykolayiv, Oleksandr Kharchenko. In 1988, at the Moscow Budinka youth there was a great exhibition of the daily mystery “Eidos” with the participation of Tistol and Reunov. That very same day, at one of the Moscow exhibitions, they met Olga Sviblova[4], who worked as a journalist on a TV station and was a current mister. The works of the Ukrainian Mitzi impressed their boards, so she took up the promotion of their creativity.

A photograph of artists from the exhibition “Kiev-Tallinn”, 1987 / Published in the magazine “Ranok”

Poster for the exhibition “Eidos” near Moscow, 1988

Although the program “Volyovaya Grani” never took shape in a letter to the manifesto, the exhibition was installed in 1989 at the exhibition hall “Kashirka” in Moscow, where the robots of Tistol, Reunov, Kharchenko, Bistrova were demonstrated and Skugareva. Archival materials about Nina’s exhibition are appreciated by doctors.

The period 1989–1991 was a fateful period for artists to see a lot of exhibitions. Among the brightest projects is the exhibition of “Furmanny Provulku” in Poland. In 1990, in the Moscow Central Booth of the artist Tistol and Reunov held a major exhibition “The Act of Artistic Opposition.”